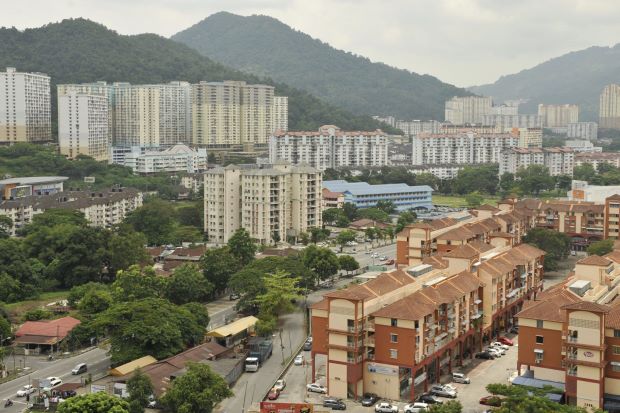

Almost all those in Farlim live in high-rise flats.

The township that is home to Air Itam’s high-rise flats is steeped in history.

LOOKING at the skyline of Bandar Baru Air Itam or more popularly known as Farlim among Penangites, with its many high-rise apartments, many among the young would probably have no inkling of the history of this township.

The land where Farlim is located was previously known as Thean Teik Estate, which was named after Khoo Thean Teik.

Thean Teik, literally translated as “heavenly virtue”, was no ordinary person. To the Chinese community, he was a businessman who used his social and clan associations to protect his business links but to the British, he was simply the leader of a notorious triad.

At the age of 34, he established himself as the Big Brother or tai kor of the Khian Teik or Tua Pek Kong secret society.

Historian Dr Wong Yee Tuan wrote in his article “Uncovering the Myths of Two 19th Century Hokkien Business Personalities in the Straits Settlements” that Thean Teik and his younger brother Thean Poh, even formed an alliance with the Red Flag, a Malay-Acehnese secret society.

More interestingly, the alliance was further strengthened when Thean Poh gave his daughter in marriage to Red Flag leader Syed Mohamed Alatas’s son, Syed Sheikh Alatas, as the latter’s second wife.

The friction between the Red Flag/Khian Teik alliance and the White Flag/Ghee Hin alliance eventually erupted into an open gang war, known as the Penang Riots.

As students of history, we would have read of the Hai San-Ghee Hin clashes. Thean Teik was aligned to the Hai San gang.

They mobilised thousands of coolies and started the street fights, the worst in 19th-century British colonial rule, in order to regain control of the opium farms.

At that time, Thean Teik was also a director of the respectable Khoo Kongsi, the clan house of the Khoos, but that did not stop the authorities from sentencing him to death.

But Thean Teik had enough clout and influence. The British colonial government even feared that his execution would lead to another riot and quickly reduced it to life imprisonment. But he was released after seven years. Another report claimed that his sentence lasted for only 18 months.

Thean Teik made his fortune and prospered by buying up vast tracts of land that came to be known as Thean Teik Estate.

Much of the money came from immigrant labour trading and opium distribution, permitted by the British. In Perak, he was also involved in gaming and pawn-broking, which made him even richer.

He was a chairman of the Penang Chinese Town Hall and a trustee of the Leong San Tong Khoo Kongsi, his family clan temple.

In fact, due to his invaluable contributions, a large estate in Air Itam owned by the family clan association, where Farlim now stands, was named after him.

A report in the Straits Times weekly (Oct 1, 1890) recorded his death and funeral with great detail.

“He was taken to his burial place last Wednesday with all the pomp and splendour which money could command to make it the grandest funeral yet seen here,” according to the report.

“A general holiday in town enabled crowds of sightseers to swell the multitudes, who gazed at the flags and banners, bands of music, gilded shrines, pigs, goats and accompanying the richly decorated coffin and taking an hour to pass.”

But the violent past and the link to Thean Teik Estate took a different form in 1982, when riots broke out at the Thean Teik Estate as developer Farlim Sdn Bhd began groundwork.

The protest led to the death of Madam Tan Siew Lee and injury of four persons, turning the confrontation into major national news.

The Star front-paged the news on Oct 30, 1982, with the headline “One Dead, 4 Hurt in Brawl” with the report that Tan was shot in the neck by police when they tried to stop a crowd of between 100 and 150 residents from attacking construction workers at the Thean Teik Estate.

The injured included three workers. One was hit by a hoe on the head during the protest in which the crowd was reported to be armed with parang and sticks. Police had to use tear gas to break up the protesters.

I was then 21 years old and still studying at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. I knew Thean Teik Estate like the palm of my hand, having used the winding trail connecting Kampung Melayu, where I stayed, to the neighbouring estate countless times.

I was familiar with the many vegetable and chicken farms in the area with its rural setting, which often gave me a sense of isolation.

Gripped by the newspaper reports of the clashes, I had wished I was at the scene to file my reports of the violence at my kampung instead of being stuck at the campus in Bangi, Selangor.

Having had a taste of journalism in 1980, when I briefly worked for The Star in Penang after I finished my Sixth Form, I became addicted to the world of journalism and could not wait to get back to work.

The demonstrations were emotional with some activists attempting to make it look like a fight between the downtrodden peasants and a rich developer, with the police siding the rich. But the reality was land had become scarce by then, and many Penangites were beginning to realise that farms had to eventually make way for flats.

Today, Farlim is home to thousands of people, almost all living in high-rise flats. And many more such buildings are being built.

No one is likely to bother about the link to the past — the connection to a wealthy businessman, of a bygone era, who led a triad and staged a full-scale war in the streets of Penang; and the violent protest just over three decades ago that captured our national attention.