IT’S been more than two years since Pastor Raymond Koh was abducted.

The police said they have been investigating and we all know nothing has come out of it despite the huge publicity surrounding the case.

The Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (Suhakam) carried out a lengthy inquiry and produced a voluminous report of more than 2,000 pages, where it bravely pointed fingers at the Special Branch as being responsible for the abduction.

Then Suhakam chairman Datuk Mah Weng Kwai described the two missing persons – social activist Amri Che Mat and Koh – as “victims of an enforced disappearance”.

The panel, he said, disclosed that individuals or groups operating with the support of state agents has been involved in the abductions (Koh in February 2017 and Amri in November 2016).

“The panel is of the considered view that the enforced disappearance of Amri was carried out by agents of the state namely Special Branch, Bukit Aman.

“The disappearance of Koh was neither a case of voluntary disappearance nor a case of involuntary disappearance in breach of the ordinary criminal law.

“The directive and circumstantial evidence in Koh’s case also proves that he was abducted by the Special Branch,” he bluntly stated at the announcement of the final findings of the Suhakam’s public inquiry on the disappearance of the two, in April.

Two Inspectors-General of Police – Tan Sri Khalid Abu Bakar and Tan Sri Mohamad Fuzi Harun – have since retired.

In fact, Fuzi was head of the Special Branch at the time of these disappearances.

And now, we have a new IGP, Datuk Seri Abdul Hamid Bador, who will have to continue what Fuzi started and where he left off.

The police have said that Bukit Aman gave its full cooperation to the Suhakam inquiry, adding that Fuzi, in fact, set up an investigation committee to track down the location of both men, prior to the results of the inquiry.

But in the absence of new leads or even progress, we can conclude that nothing concrete has been revealed after two long years.

There has been no closure.

The police owe Malaysians – not just the families of Koh and Amri – an answer.

This is Malaysia, not some lawless South American country where people are grabbed and taken off the streets, either by criminals or law enforcement agents.

This is not allowed over here.

We are not interested in the political or religious approaches or tactics of the two, if there were any, as we view them as ordinary human beings.

Our fellow Malaysians. Tragically, no word has been forthcoming from the authorities.

But Koh and Amri should not be allowed to be forgotten.

The two will remain in our memory and in our cry for the truth to be told, although there are powerful, dark forces bent on stopping or ending it.

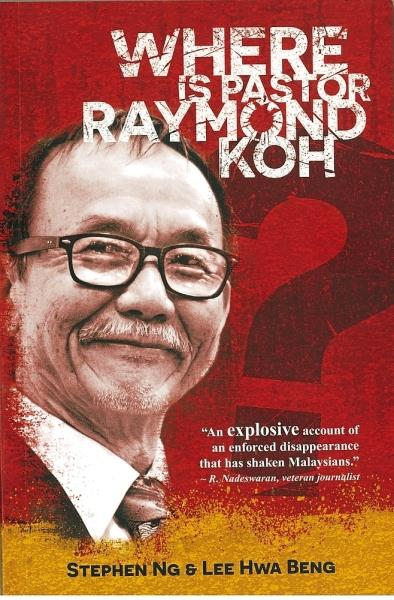

A 182-page book, simply titled Where Is Pastor Raymond Koh, written by Stephen Ng and Lee Hwa Beng, will be launched on July 3, although the publication, the first comprehensive one of the abduction, is already in major book shops.

The book is essential and timely as we want to embrace the values of a New Malaysia, and surely, the new government is expected to pursue justice for the long-suffering families.

The time is also right for us, as a maturing democracy with greater space, to openly discuss issues of this nature.

Yesterday, Home Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin announced that a six-man special task force to probe the alleged enforced disappearances will be headed by former High Court judge Datuk Abd Rahim Uda and expected to report its findings in six months.

For the writers of Where Is Pastor Raymond Koh, they have made an obvious effort to be neutral and produced an objective book with no political undertones and rhetoric.

Indeed, as responsible citizens, we want the police to successfully conclude their investigation and even as aspersions are cast, we believe the police force under the leadership of Abdul Hamid must be given every opportunity to provide justice for the families and to uncover the truth.

In the words of the authors, we have “to work together to bring our Royal Malaysia Police to greater heights of excellence”.

The Suhakam inquiry report has put a big blot on the police’s image but moving forward, the force must be resolute in purging rogue members, or in plain language, crooks in uniforms, and deliver the trust and confidence back to the force.

The book, which chronicles the events leading to and after the abduction, is a compelling read for ordinary but right-thinking Malaysians who feel a sense of restlessness in our hearts following the episodes.

Surely, we must have a conscience, a sense of sympathy, for the family members of Koh and Amri, who walked out of their homes one day and have since not returned.

Surely, they deserve better answers than to be told regularly that “kes ini masih dalam siasatan” (the case is still being investigated).

The point here is this – it should not have happened to Koh and Amri, and it should not be allowed to happen again, to any Malaysian, no matter how much we disagree with, or even despise strongly, what they advocated.

No one should attempt to play God, and to pass judgement on anyone because there is only the one God, who we will all be answerable to.

And as the faithful, regardless of our faith, we know the answers will surface eventually.

It has taken Ng, a media consultant and writer, who studied chemistry, and Lee, a former state assemblyman and an accountant, to put together this book, an effort almost journalistic in nature.

The book will be launched at the Council of Churches of Malaysia by Rev Julian Leow Beng Kim on July 3.