We need our leaders to set the tone and directions right, as no one should experiment our children’s future as the whims and fancies of our ministers.

Education has kicked into high gear in most parts of the world, yet in Malaysia, we’re still aimlessly cruising the neighbourhood.

A FEW years ago, I visited a school in Guangzhou where I was privy to the scenes of a robotics lab where students were busy trying their hand at operating some of the models. In the class next door, the teacher was guiding teenage students on 3D printing processes, which is used to create three-dimensional objects from a computer-aided design model.

The school administrator also impressed upon me that they were using the STEAM education approach to learn the uses of Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts and Mathematics as access points for guiding student inquiry, dialogue and critical thinking. By no stretch of the imagination was the modern education facility a representation of schools in China, because it’s an elite school in an urban setting. However, I was told the Chinese government is very focused on what they want, and this is the way things are taking shape.

It’s refreshing to see that’s the kind of education reforms China has been working on. They spend little time on irrelevant education issues like Malaysia is famous, or infamous for.

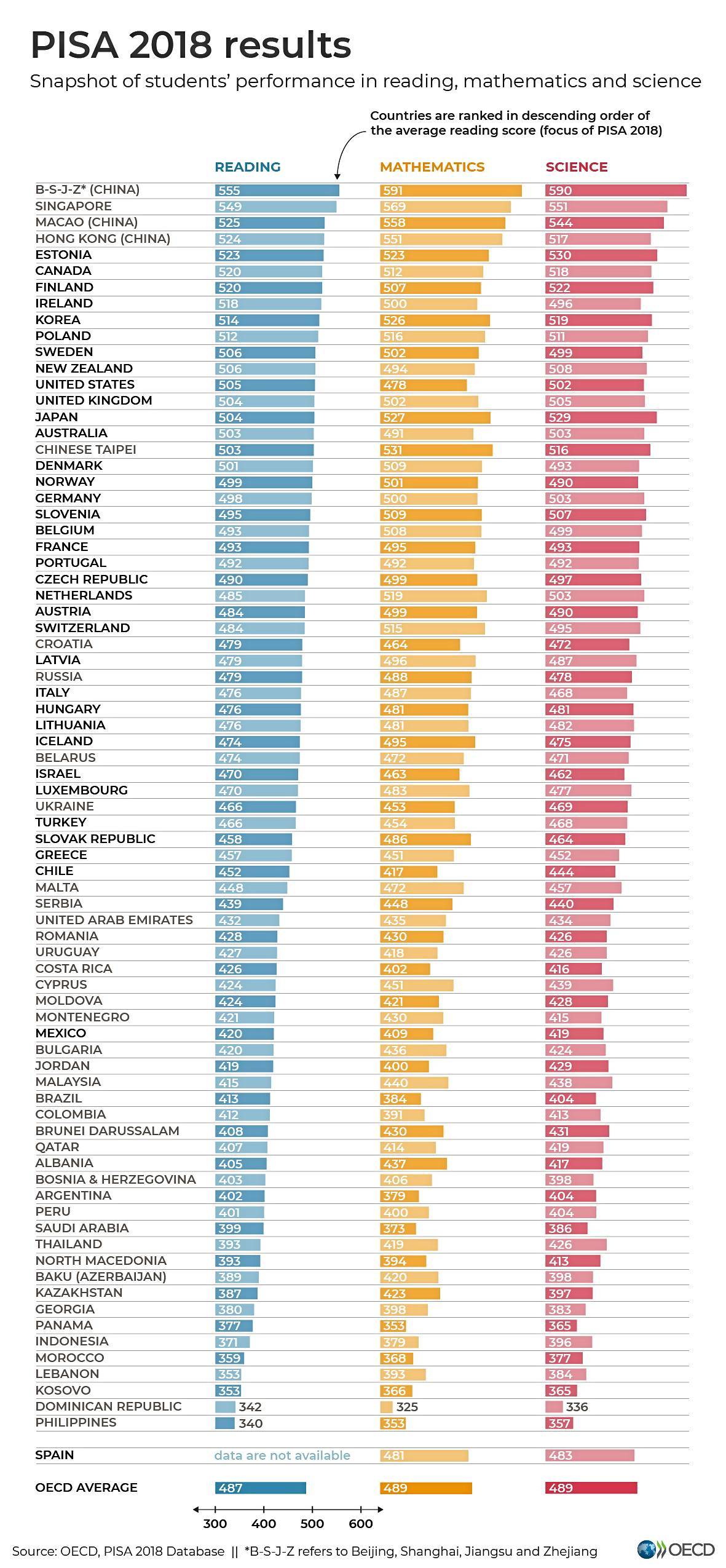

So, it comes as no surprise that a global education study has revealed that Chinese students in most of the country’s cities have outstripped their counterparts in nearly all parts of the world, as far as important skills in the information age is concerned.

According to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) ranking in 2018, some 22% of the 15-year-olds surveyed in Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces, showed they could handle abstract concepts and discern facts from opinions in what they read by achieving a reading level of at least 5 out of 6. Only Singapore fared better, with 26% of the city state’s students reaching the mark, while the overall average was 8.7%, according to test results released recently.

Pisa says this skill is becoming increasingly important as technology allows easy access to information. Reading, on the other hand, has become more about building knowledge, thinking critically and making well-founded judgments, rather than extracting information.

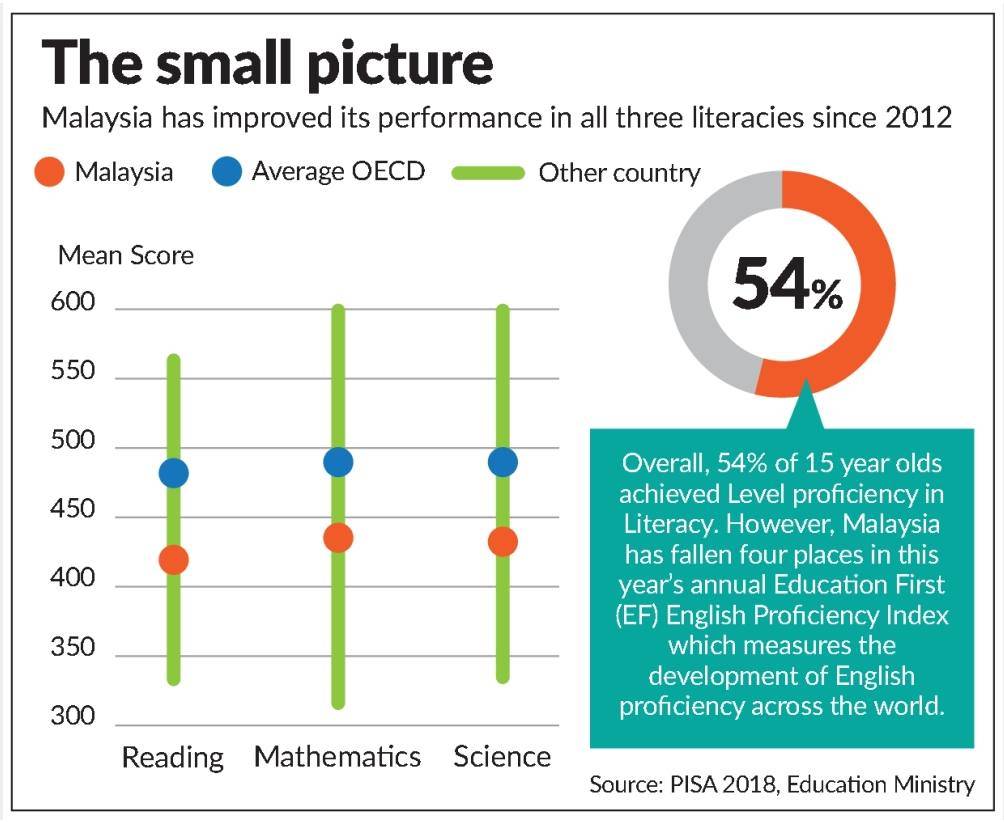

By now, most of us have read about Malaysia having moved up into the middle-third of the international assessment for participating countries, having advanced from being in the bottom-third in previous cycles.

Thank goodness we have improved, and it’s commendable that we are vying to improve our ranking by the next two cycles.

Education director-general Datuk Dr Amin Senin said Malaysia is headed in the right direction of education system reform.

According to him, its performance in the 2018 PISA was deserving of a significant improvement in ranking for all three domains – Science, Mathematics and Reading literacies.

Based on results released by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), he said Malaysia scored 440 in Mathematics, 415 in Reading and 438 in Scientific literacy in PISA 2018.

This charts a course of improvement for Malaysia from PISA 2012 and 2015, when our country achieved below the global average score.

“Overall, Malaysia’s achievement showed significant increase in all three domains.

Some of us have found pride in that, but when looking at how Malaysia has ranked in the overall list, it shows that we’re barely at the races, and that we have an uphill battle ahead, even as we do all we can to catch up. Honestly though, it’s simply not good enough.

The Malaysian media conveniently omitted the entire ranking table of the participating countries, which would have given us a proper perspective of where we stand in the world.

We were quite content to report these findings for having walked the talk. It’s not wrong, of course, and we should encourage our educators as they connect the dots of our education system, while doing their absolute best under such testing circumstances.

But in Australia, the media was outraged that it’s falling behind other countries, lambasting themselves for their ranking and even branding themselves dumb. It was the hottest news, and that’s understandable because Australia prides itself as a global education hub attracting students from around the world.

In Malaysia, it isn’t Maths and Science that we’re struggling with, but English proficiency at global level.

Last week, it was reported that Malaysia has fallen four places in this year’s annual Education First (EF) English Proficiency Index, which measures the development of English proficiency in the world.

It was revealed that while it’s third in Asia, behind Singapore (66.82) and the Philippines (60.14), Malaysia’s score of 58.55 has seen it slide from the 22nd position to 26th in the latest edition of the rankings produced by international education firm EF Education First.

While it didn’t elaborate, the report stated that in Malaysia, men outscored women in English proficiency by a significant margin.

The index, currently in its ninth year, was created after analysing the EF Standard English Test scores of 2.3 million adults from 100 countries and regions.

The future is in robotics, artificial intelligence and machine learning, all of which are inextricable from various occupations.

In Singapore, driverless vehicles are seeing trial runs in campuses. Malaysians, though, have been left to wonder when such scenes will appear in our many local universities, since some have been pathetically engrossed in allowing racists to rant insensitive communal remarks with no real economic programme produced in academic form.

Is our education system, be it in schools or universities, preparing our students for the next stage, where job demands have changed, or, are the same teaching modules and lecture notes being recycled?

Is it surprising when we read about our graduates being jobless, and we know that many of them lack the soft skills required in the private sector – proficiency in English, and now Mandarin, talent in leadership, creativity, innovation and communications, and even ethics?

Those of us who studied for the Malaysian Certificate of Education (MCE) and Higher School Certificate (HSC) are aware that standards then were high, and a distinction was equivalent to the O and A levels, which are still intact in the UK.

Today, we have compromised, and some would even say, tampered with our grading system to the point that the string of distinctions obtained by our students at SPM and STPM levels are unceremoniously ignored by international institutions. An “A” in English is probably a “D” by UK standards.

And so, we have a false sense of achievement, and worse, unrealistic expectations, whether as students or parents, for believing we’ve done well and deserve rewards in return, when, in truth, we haven’t done enough at all.

Sarawak announced that it will now use English for Maths and Science, but does it help when state Education, Science and Technological Research Minister, Datuk Sri Michael Manyin reportedly said that students should not bother about English grammar.

Of course, it matters. It’s the basics in learning English. We can’t accept compromises with such comments like “don’t bother about English grammar. Don’t bother about the Queen’s English, just use Sarawak English.” So, let’s nip this in the bud from the start.

We need our leaders to set the tone and direction right, as no one should experiment with our children’s future based on the whims and fancies of our ministers. When we should be emphasising the importance of science, maths, AI and robotics, why are we, instead, telling students in schools to wear black shoes, or learn martial arts, regardless if it’s silat or kung fu?

Sure, more peculiar things may have happened in this country, but this ranks up there in the strange stakes.