IT’S ironic that a controversial statement by Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, largely forgotten or more precisely, generally unknown to most Malaysians, would get resurrected.

And even more coincidental that it must come from his daughter, Datuk Paduka Marina Mahathir, who mentioned it in her column in this newspaper.

The editor who cleared her copy was probably not born yet to be able to spot Marina’s error.

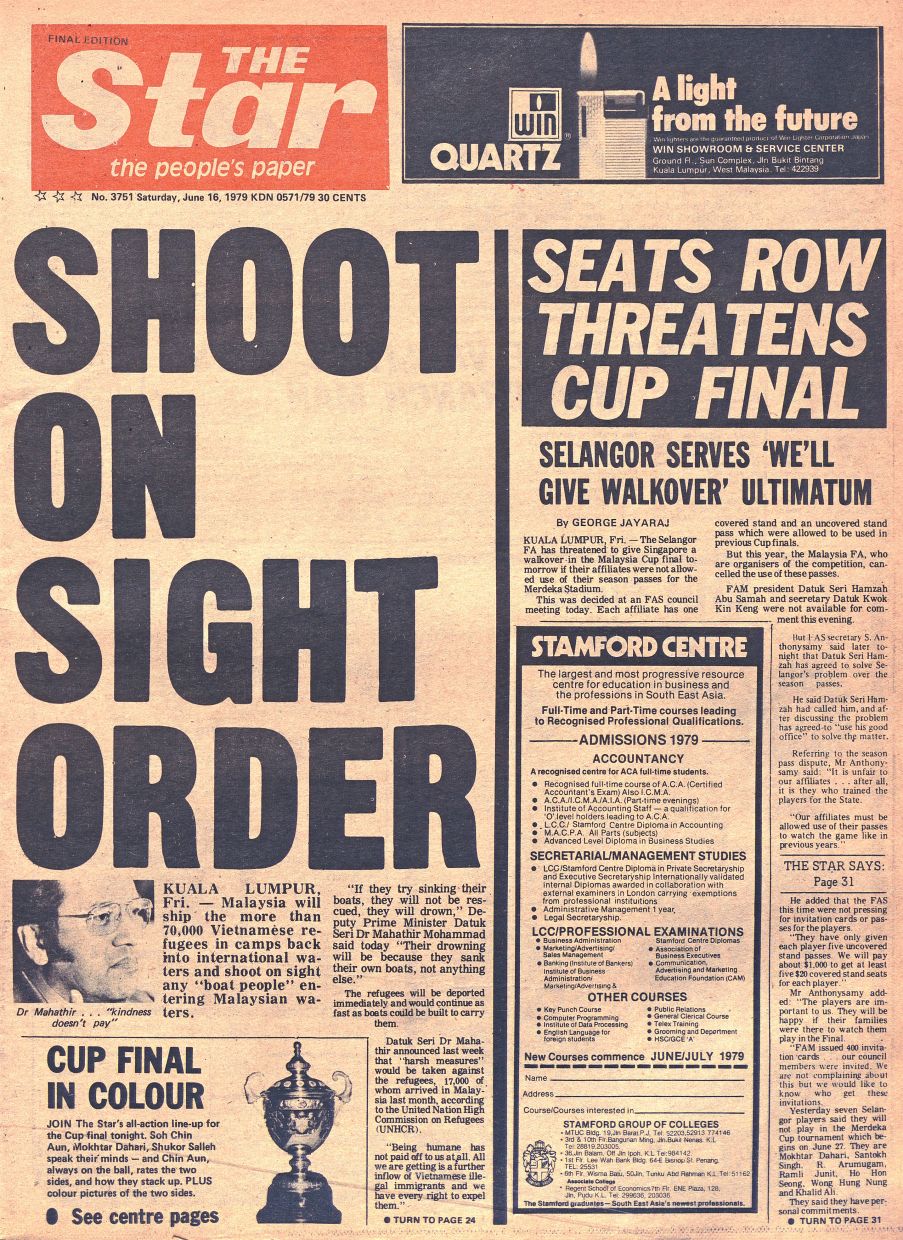

The crux of the issue is that Marina had wrongly attributed a “shoot to kill” threat made by the then Home Minister, the late Ghazali Shafie, in the 1970s regarding Vietnamese refugees.

Explosive affair: Dr Mahathir’s statement in 1979 caused an uproar all around the world, sending the people around him scrambling to clear up the mess.

The “shoot to kill” threat was reported in the media to have, in fact, been made by then Deputy Prime Minister Dr Mahathir, her father.

Malaysia made world news for that remark and as usual, for the wrong reasons, a long-running and familiar theme.

I was just an angsty 18-year-old Sixth Former who spent more time reading the newspapers than textbooks.

I remember reading the gaffe by Dr Mahathir, which angered me, although I can’t remember the subsequent details.

Those of us from that generation would recall the Vietnamese refugees, known as Boat People, who began landing on the East Coast beaches in their rickety boats in 1975.

Many perished on their voyages through the rough South China Sea while trying to escape the communist rulers and soon, Pulau Bidong, off Terengganu, was turned into a refugee camp from 1978 to 1991.

Later, a transit camp was set up in Sungai Besi, Kuala Lumpur, as well as seven other camps in the east coast, Sabah and Sarawak.

The camp in Sungai Besi, set up in 1982, was officially closed in 1996 with the repatriation of 22 boat people to Hanoi, the last batch of refugees to leave Malaysia.

By that time, Malaysia had sent 248,194 people to third countries and repatriated 9,592.

In the 80s, many of us driving past Sungai Besi could clearly see the camp. I was assigned by The Star to visit some of these repatriated refugees in Vietnam, ahead of the country’s admission into Asean in 1995.

They were happy to talk to a journalist from Malaysia who showed interest in how they had fared.

Digging into the archives, I interviewed Bui Huu Duyen in Ho Chi Minh City, who said he picked up Bahasa Malaysia from watching television and conversing with the camp policemen.

He was only 16 years old when he fled Vietnam, but it had nothing to do with politics except to migrate to the United States. He jumped on a crammed boat with 200 people on board. After years in Malaysia, he agreed to go home, only to find Russia was no longer communist, Vietnam asylum seekers were no longer automatically considered refugees, a status which would be a passport to resettlement in the West, and Vietnam had launched its doi moi (economic reconstruction) to welcome capitalists.

But not all was rosy. In 1995, over 4,000 refugees tore down the fence at the Sungai Besi camp and even disconnected the power supply in a protest against their return to Vietnam. There were reports that home-made weapons were found.

His years in Sungai Besi, where he learnt English, helped him get a job as a driver.

However, the late 1970s were turbulent times, when boat people began to land on our shores, which tested how Malaysians were going to handle these unwelcome visitors.

The toxic elements of race, religion and politics all came into play, as is expected in Malaysia. In fact, it’s still happening today, as we’re well aware. All this became an explosive affair when Dr Mahathir made that remark.

In her column dated Jan 30, Marina said, among other things: “I’ve been through embarrassing moments abroad when our politicians have said something stupid and then tried to cover it up.

“In the late 70s when we had many Vietnamese refugees landing on our shores, our then home minister announced that we would shoot any that washed up on our beaches.

“Predictably, outrage ensued around the world. He then gave the standard politician’s excuse, that he was misquoted, that he actually said he would ‘shoo’ them away. Did anyone believe it?”

In a Facebook post subsequently, Marina thanked all those who had pointed out the “major factual mistake” in her column, adding “it seems that I’m capable of making my own gaffes, so I stand corrected and sincerely apologise.

“It was not meant to revise history, as some have alleged, it was wholly the weak memory of something that happened when I was barely out of my teens and still trying to make sense of the world.”

It’s understandable. Even the copy clearer at The Star failed to notice the error and in normal cases, the editor would have corrected it and informed the writer.

The uproar caused by Dr Mahathir led to then Prime Minister Tun Hussein Onn reportedly rushing to reassure then UN secretary-general Kurt Waldheim in a letter that there was no such policy.

“I wish to state that our measures to prevent further inflow of the boat people do not include shooting them,” Hussein said, according to news reports.

The Washington Post report noted that Hussein’s statement contradicted Dr Mahathir’s words, “who according to several news agencies, threatened that new refugees would be shot and that the estimated 75,000 in camps here would be put back to sea”. He also was reported to have said that Malaysia was building a fleet of boats.

Last week, veteran journalist Rajan Moses, who was then with Bernama, revealed how he was “punished” for reporting squarely about comments by Dr Mahathir in 1979 that the boat people would be shot on sight to prevent them from landing on Malaysian shores.

Moses said: “I was the only journalist, a Bernama journalist at that, who actually wrote the ‘shoot on sight’ story based on what Dr Mahathir said to a few reporters at the UKM news conference in June 1979.

“It made world headlines. The Bernama story (my story) was played up well, but later was re-edited and tempered to take out the sting in the original story,” he reportedly explained in the Malaysia First chat group, whose members broached the issue.

All this is history, but the controversy has helped put the missing pieces of the jigsaw puzzle together so we can have a better and accurate understanding of the past, and hopefully, a better way of handling similar incidents in the future.

As for me, I’m more worried that our politicians have continued to shoot themselves in their foot and drag the country down.

Just a few years back, my church had to shut down its Vietnamese ministry when almost all the workers had returned home because their country had progressed and moved ahead in Asean.

In just a few decades and despite the wounds of the war, Vietnam has blossomed impressively. It has consistently been among the fastest growing economies in the region in terms of GDP growth, foreign direct investment, and middle-income population.

It’s shaping up as the region’s single economic success story in the coronavirus era, according to asia.nikkei.com.

We have plenty of reasons to be concerned. We can’t even beat the Vietnamese in football now.

Excessive, unconstructive politicking in a democracy does have many pitfalls. Perhaps it’s time we shoo away these politicians. Or shoot them down via the ballot boxes.