Digital fentanyl: We have all become addicts to social networking, making many fear losing access to these platforms if they fall foul of their rules or guidelines, says the writer. — 123rf

DEPENDING on which side you are on, the late Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh, who was assassinated last week, was either a hero who defended the Palestinians or a leader of a terrorist group.

But as far as Meta, the parent company of Facebook, is concerned, it is the latter; as the Prime Minister found out much to his disgust, his posting on the Hamas leader was deemed unacceptable and was deleted immediately.

The removal notification from Instagram stated that Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim’s post contained “symbols, praise, or support of people and organisations that we define as dangerous.’’

So much for the freedom of expression. If that’s not censorship, we do not know what is. Or maybe it is simply that the political stand of the PM is not aligned with what the owners of these social media platforms subscribe to.

It may seem ironic, but in the eyes of these operators, the PM’s posting was defined as more dangerous than the scammers, bullies, sex predators and anonymous slanderers roaming freely in cyberspace.

Over the past one year, many netizens have found their postings in support of the Palestinian cause removed, but we are helpless, because we do not have alternative social media platforms as in China and Russia.

Last week, Bersatu president Tan Sri Muyhiddin Yassin’s statement on Ismail was also removed from Facebook. Dewan Rakyat Speaker Tan Sri Johari Abdul also suffered the same fate.

The reality is the world is dependant, if not hooked, on Facebook, Instagram, Google Chat, TikTok, Telegram and X (formerly Twitter).

While many of us have criticised the government for its plan to impose regulations on these platforms from Aug 1, these critics have strangely been silent when postings supporting Hamas leaders or the Palestinians are removed.

Neither has there been any objections or anger towards the many cyber criminals, who operate behind anonymity, who scam, cheat, bully or defame innocent people daily,

Perhaps that’s the idea of the “freedom of expression”, that these platform owners should be left to operate without rules, and allow them to cause misery, humiliation and even death.

These operators have become so powerful that any form of government intervention is regarded as unpopular and opened to criticism by groups or personalities who only look at one issue – politics.

While no one wants dissenting views to be curtailed, let’s not forget the real anguish affecting common folks daily.

We have all become addicts to social networking, including this writer, and many fear losing access to these platforms if they fall foul of their rules or guidelines.

It is what has been called “digital fentanyl” or an addiction to these destructive platforms. The US legislators used this term to describe TikTok, but they turned a blind eye to the other platforms, which aren’t any different.

Fentanyl is a synthetic drug, which the Americans are fond of accusing the Chinese government of providing to Americans, and the reference to TikTok is because the short-form video hosting service is owned by Chinese Internet company ByteDance.

Many accusations have been levelled at TikTok and Huawei for their purported access to the data of Americans using these tools, but doesn’t Meta, for example, also already have our details?

In the words of Malaysia Communications and Multimedia (MCMC) commissioner Derek Fernandez, “the customer was sometimes viewed as a product whose data is traded for the right to use the service rather than a human being who must be protected from the dangers and predators in the digital space.’’

He said they see customer security as “a cost and not part of digital infrastructure needed to generate the huge profits they enjoy.”

To put it simply, these operators feel that it is the job of governments to regulate cyberspace and that it’s not their job to police cyberspace.

Neither is it their worry when people conceal their identities, create multiple accounts, target vulnerable people and deploy scam technology but when proper regulation is initiated, they cry “violation of freedom of expression,’’ knowing they will have their chorus boys.

“There have been clearly insufficient resources allocated by digital services providers for cybersecurity,’’ said Fernandez, adding that the problems have grown to the point of society being threatened and governments have realised that intervention was not only necessary “but a sovereign responsibility of the nation.’’

The cybersecurity expert said while these platforms were heavily regulated in the European Union, US, Vietnam, Indonesia and even Singapore, “sadly they have been enjoying exemptions from licensing or even proper registration in Malaysia.’’

He also said many users were not aware that platforms required them to consent to monetisation of their personal data as “a precondition to use their services’’ and “this allows them to sell their data to third parties, and should the data fall into the wrong hands, the data can be used for targeting individuals of cybercrimes.’’

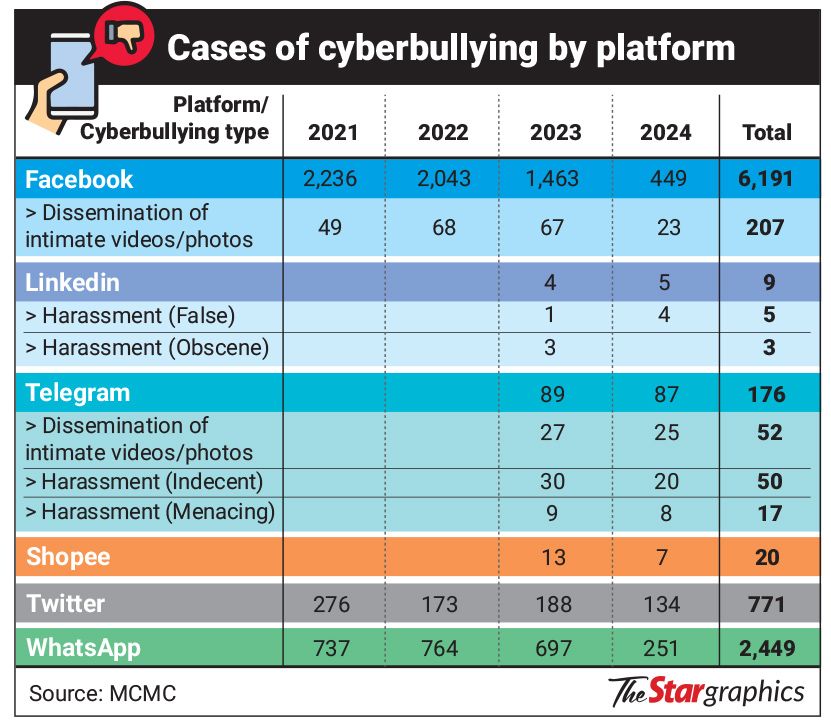

But cyberbullying in Malaysia has gone out of control. It is not surprising to detect such devious acts in Facebook or Instagram, but it has even spread to LinkedIn, which is mostly used by adult professionals.

It is imperative that various laws are updated as the term “cyberbullying’’ is not defined under Malaysian law and is generally understood to mean bullying with the use of digital technologies.

It is time that cyberbullying is more clearly defined in our jurisdictions that seek to prohibit, regulate or sanction such behaviour as well as stronger criminal punitive actions against those who heaped financial misery as well as those who spew religious and racial hate online.

Enough is enough.