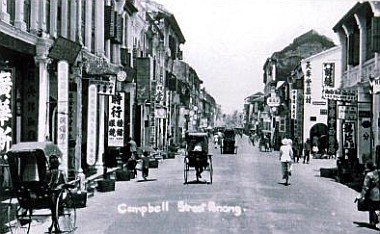

Good ol’ times : An old postcard showing rickshaws plying Campbell Street in Penang from the book ‘Penang – Postcard Collection 1899-1930’. — Courtesy of Malcolm Wade

Good ol’ times : An old postcard showing rickshaws plying Campbell Street in Penang from the book ‘Penang – Postcard Collection 1899-1930’. — Courtesy of Malcolm Wade THANKS to the old Penang’s status as a bustling metropolis and port, the island was already exposed to foreign culture long before the rest of the country. From hotels, where social events were held, to seedy bars for lonely sailors, Penang had it all.

George Town was in fact conferred city status by Queen Elizabeth II in 1957, making it the first town in the country to achieve city status — which explains why many Penangites are not overly excited with the need to apply for city status today.

In short, it was a real happening place. And right in the heart of it all was Campbell Street, which was a new road created between Pitt Street — now renamed Jalan Mesjid Kapitan Kling — and Penang Road in the mid-19th century.

Campbell Street is named after Sir George William Robert Campbell, who was also the acting Lieutenant Governor of Penang between 1872 and 1873.

According to local historian Khoo Salma Nasution, for the local Hokkiens, sin kay or new road, by way of pun, came to refer to the fresh prostitutes or “new chickens” brought in from China to fill the courtesan quarters along this street.

Campbell Street, with its many goldsmith and textile shops, was a shoppers’ paradise from the 1960s to the early 1980s. But it had a reputation for being a red light district even much earlier, and flourished as one until the war.

“The houses of pleasure were identified by red lanterns hung at the door. Senior citizens recall these dens as places to relax and enjoy a range of services. The well-dressed, well-mannered courtesans served opium, tea and liquor, and provided musical entertainment and companionship,” Khoo said.

But George Bilainkin, who was appointed as editor of Penang’s English newspaper The Straits Echo, in 1929, had a less romantic description of Campbell Street. The brash and young Briton reported that in many of these brothels there were prostitutes “as tender an age as 10 or 11 are to be found. Sometimes they are sold by their mothers and grandmothers for as little as £10.”

He wrote that “European residents in northern Malaya are careful not be seen anywhere near these houses, but visitors are not so discreet and, at times, the police have exceptionally delicate tasks to perform.”

Present time: What Campbell Street looks like now.

Present time: What Campbell Street looks like now. It is clear that the old Penang wasn’t just exotic but truly erotic.

Most present-day Penangites are probably unaware that from the late 19th century to the 1940s, before the war, there was a sizeable Japanese community in that part of town. To be precise, in 1910, the official census counted 207 Japanese residents in Penang, mostly poor settlers trying to find fortune in the lively port city.

According to researcher Clement Liang, many of the Japanese were involved in the flesh trade, with 28 such “business establishments” recorded with four male staff and 126 females.

Many of these prostitutes came from Kyushu, the Shimabara peninsula located in Nagasaki prefecture, particularly in the impoverished areas of Karayuki-San in Japan.

“Today, visitors to Tennyo Temple, a Buddhist shrine in Kyushu can witness hundreds of stone pillars engraved with the names of Karayuki-San, former places of occupation and the amounts of donation. The word ‘pinang’ is featured prominently on many of the pillars there, a testimony to Penang’s past link with the Karayuki-San which originated from this area,” Liang wrote.

He wrote that many of the farmers’ daughters were sold overseas as prostitutes with false promises of decent jobs.

Campbell Street is connected to Cintra Street or Jipun Kay while the nearby Kampung Malabar, so named after the Malabars from southern India, was known as “Jipun sin lor” or the Japanese New Road, with reference to the Japanese-run brothels and small sundry shops.

“The locals could recall that Cintra Street was a favourite place for the foreigners and non-Chinese looking for sex because the Japanese prostitutes did not turn them away like the Chinese do. These Karayuki-San were deemed cleaner as they inspected the client beforehand and refused those whom they saw carrying diseases,” Liang wrote in his paper on the pre-war Japanese community of Penang.

But by 1920, the Japanese government through collaboration with the British administrators who were concerned with the epidemic spread of venereal diseases, began to abolish this flesh trade and forced the Japanese prostitutes to leave the Straits Settlements and the Malay states.

“Most of them were repatriated to Japan for good and for those who refused to return, they either went “underground” and turned to sly prostitution or married locals to stay on,” he wrote.

Not all Japanese were involved in immoral activities, with the records showing many ran dental clinics, dispensaries and photo studios.

The Japanese were among the first groups to bring in the silent movies to Penang. One silent movie cinema owned by the Japanese was operating in Kuala Kangsar Road, near the Komtar building.

But all the excitement in Campbell Street is gone today. With the emergence of the many shopping malls in Penang, there are few reasons to shop at this once colourful and vibrant street.

Even the efforts of the Penang Island Municipal Council to build a RM2.3mil pedestrian walkway failed to bring life to Campbell Street. At night, once the shutters come down, the street is quiet and distinctively lonely with little life.

For this writer, the only chicken that makes him want to go back to Campbell Street is the one served at the century-old Indian Muslim Hameediyah Restaurant. The fried chicken and curry chicken dishes are among the best I have eaten.

And I do have many fond memories of this street. It was at one of the jewellery shops that I bought two tiny diamonds worth RM1,000 – a hefty sum then for this salaried man — for our wedding rings.

I can no longer recall the name of the shop and it has not become an issue during Valentine’s Day, which happens to be our anniversary, because my wife has forgotten too.

My mother, Yeoh Poh Choo, grew up in nearby Chulia Street, and was naturally a familiar face in the area. She used to shop for food at the Campbell Street wet market and we were always amazed at how she came back with such good bargains and occasional freebies, either some extra meat or prawns, thrown into her basket.

The Campbell Street wet market continues to be popular today and its Victorian-style architecture has provided its facade with a heritage image, similar to the Covent Garden in London.

I also remember the many hawkers who ply the street in their three-wheeled vehicles, including the kueh kak seller (fried carrot cake) who was arrogant because he always had a long queue of customers, to the curry mee seller, who would always have her entire brood with her.

Back in those days, my mother bought her own textiles to make clothes and she would bring me along. And to prevent me from getting bored, she would treat me to the dried and pickled fruits from a shop there.

All these memories and more are good enough reasons to still visit this historically-rich street each time I am back in my hometown.