Oldest church: Penang's first independent English newspaper, the Pinang Argus, was published from 1867 to 1873 and named after Argus Lane which was just behind the Cathedral of the Assumption (pictured).

PENANGITES are known to be outspoken, fiercely independent-minded, and highly liberal. It comes as no surprise that the state was where many non-governmental organisations had their origins, long before civil society became the fashionable political term it is today.

Penang is also where the country’s earliest newspapers were founded and has produced some of the most prominent activists and writers. As one of the earliest British settlements in the region, Penang has the distinction of producing the first English newspaper in the country.

According to historian Geoff Wade, the Prince of Wales Island Government Gazette published its first issue in 1806 and was published continually until the early 1830s.

“The period over which the newspaper was produced saw great change in Penang and more broadly in the peninsula, and The Gazette was one of the few public records of these changes. By providing a public medium for the exchange of information and ideas, the newspaper also brought new knowledge systems and new ways of knowing to a range of people within the society, albeit an elite, and thus must be seen as a major element in the introduction of modernity to the peninsula.

“The contents of this journal, and the interests and concerns expressed, provide us with a valuable source for examining various phenomena of early 19th century Malaya and particularly the important entrepôt that was Penang.

“These range from the concerns of the East India Company administrators as seen through their public announcements and orders, the economic bases of the society observed through shipping news, price current lists and auctions of the revenue farms, and social clashes noted through the crime reports,” he wrote.

According to Boon Raymond, the Gazette was not a government publication but a private initiative led by one Andrew Burchet Bone or A.B. Bone.

“Mr Bone had been a printer in India and brought his skills to Penang where he began to utilise his Indian experience. Mr Bone was also engaged in a business partnership with a Mr Court, and their firm “Court and Bone” was one of the major auctioneers in Penang in the first decades of the 19th century, frequently advertising on the front page of the Prince of Wales Island Government Gazette, the name which the newspaper adopted on 7 June 1806.

“This title was subsequently shortened to Prince of Wales Island Gazette (PWIG) in October 1807.”

There were also other firsts – the state’s first independent English newspaper, The Pinang Argus, was published from 1867 to 1873. According to Khoo Su Nin’s Streets of Georgetown, it was at Argus House located at Argus Lane that the newspaper came into being, hence its name.

This was where the state’s earliest Eurasian Catholic settlement was set up.

Despite its historical significance, there are no indications of the building today.

Argus Lane is located off Love Lane near where the 160-year-old Cathedral of the Assumption, which is the oldest church in Penang, is located.

As a student of St Xavier’s Institution, I had spent much time in the area and would go often to the church to pray for divine intervention as I faced the many examinations which still give me the occasional nightmares in my adult life until now. Some of my Eurasian friends and school mates also lived at Argus Lane. Penang is truly the place where the printer’s ink flowed freely.

From 1806, when the Gazette came into being, right up to the 1970s, there were 27 English newspapers published, according to Boon.

They included the Pinang Register and Miscellany, Government Gazette of Prince of Wales’s Island, Singapore and Malacca, The Pinang Gazette, Daily Bulletin, Indo-Chinese Patriot, Eastern Courier, Malayan Ceylonese Chronicle and the Straits Echo.

Within walking distance from Argus Lane is 120, Armenian Street – the birthplace of the world’s oldest surviving Chinese newspaper, the Kwong Wah Yit Poh, since 1910.

The daily was founded on Dec 20, 1910 and masthead in use today was a calligraphy personally written by Dr Sun.

It was during his exile in Penang, as a Penang tourism website rightly puts it, “that history was shaped here – right in the humble rooms of this double-storey shop house where China’s first elected provisional president, Dr Sun Yat Sen held important meetings that helped change the face of China’s political and social structure.

“It was here — the Nanyang headquarters of the South-East Asia T’ung Meng Hui (a revolutionary party led by Dr Sun before China became a republic) that the great leader of the Chinese nationalist revolution held the momentous “Penang Meeting”.

“Held on the 12th day of the 10th lunar month in 1910, the meeting saw members of the T’ung Meng Hui planned the Canton Uprising in 1911 that eventually led to China becoming a republic in 1912.”

Any article on Penang newspapers would be incomplete without the mention of The Straits Echo, which was one of the oldest newspapers in Malaysia.

The Echo, which began in 1903, had a most illustrious history until it officially closed down in 1986.

Some of my colleagues actually cut their teeth in journalism at this newspaper, which was renamed The National Echo when it became a tabloid and went national in the early 1980s.

Even after going national, the fight between The Echo and The Star was in Penang, with both championing their Penang roots. There was no love lost between the two newspapers and one of the most interesting battles was to bring out their street editions first.

The early history of the newspapers in Penang has been well-documented by two of The Echo’s editors – Manocasothy Saravanamuttu in The Sara Saga and by George Bilainkin in Hail Penang! Both books are published by Areca Books. In her review, Kirsty Walker wrote that: “The Sara Saga and Hail Penang! are autobiographical accounts written by journalists who both served, at different times, as editor of the Penang-based newspaper – Straits Echo – during the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s.

“Through witty anecdotes, Manicasothy Saravanamuttu and George Bilainkin related their experiences and encounters in early 20th century Penang.

“As journalists, they were able to observe many of the key moments that shaped Malaysia’s history. Through their eyes, the reader gains access to the intimate workings of Penang’s interwar colonial society, the horrors of the Japanese occupation, and later, the rapid changes brought about by Malaysian independence.”

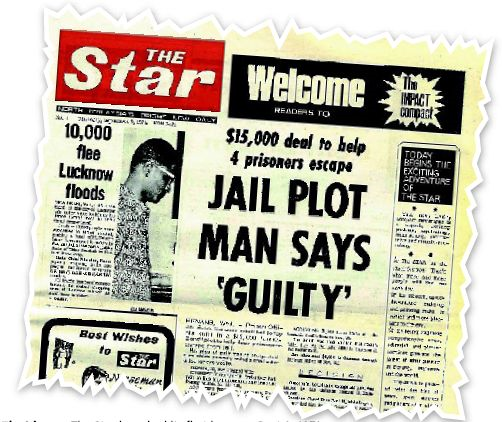

And of course, we have The Star, which was founded in Penang by KS Choong, which hit the streets on Sept 9, 1971, from its original seafront office in Weld Quay, it moved on to Pitt Street or Jalan Kapitan Keling where it grew from strength to strength to what it is today — the country’s biggest English daily.

According to a news report quoting then news editor K. Sugumaran, Sept 9 was the birthday of the founding editor Choong. Some of the biggest and best journalists in Malaysia who started in that tiny office in Weld Quay included Sugu, M. Menon, Khoo Kay Peng and Charles Chan.

Interestingly enough, Choong later went over to The Echo when it switched from broadsheet to tabloid to fight the paper he founded.

As a student of history and a history buff, I am glad that I am in a profession where I have a ringside seat to witness and record history as it happens. These are magical moments indeed.