It’s hot and dusty in the sprawling plains of the Serengeti in Tanzania. The dry season has gone into overdrive at this time of year, but August is also the best time to be on the safari trail.

This is when the greatest animal spectacle on Earth begins as wildebeest herds begin their massive migration across the crocodile-infested Mara river in search of water and greener pastures in Kenya.

It had taken a year for me to plan this trip – including saving enough money – and to visit this part of East Africa.

Tanzania is the envy of African nations as it is home to the best-known wildlife sanctuaries, including the Serengeti, Ngorongoro Crater and Kilimanjaro.

Some 20% of Africa’s large mammal species roam the reserves, conservation areas, marine parks and 17 national parks, all spread over an area of 42,000sq km, and forming about 38% of the country’s territory.

I first met Charles Mpanda – a hulking Masai safari operator – at a restaurant in Bangsar.

No surprise then that he was still wearing his safari hat and bush attire in Kuala Lumpur when I was introduced to him by a former Cabinet Minister who had travelled with him and insisted I do likewise.

After listening to him, I was convinced my group of Malaysian travelling companions would be in safe and competent hands.

After all, Charles was also endorsed by my idol, the famous off-the-track traveller-photographer Yusuf Hashim.

Lions don’t normally roam the plains if they are not hunting for prey.

“But Charles, I am very focused. I want lions. I don’t care about zebras and elephants. Can I see them?” I queried impatiently.

With a serious face, he responded calmly by telling me that I needed much patience to see them up close, and not just 10 feet away.

Of course, this advice is easier offered than taken, but nonetheless, I developed plenty of patience with the endless waiting under the hot sun, while needing to remain silent to spot these big cats and not spook them. It was all about searching, searching, searching and waiting, waiting, waiting.

In the 12 days I was there, my party located eight lions, which included two males. They looked elegant and impressive with their distinctive manes, truly giving them the aura and look of the King of the Jungle.

Larger, stronger and certainly more muscular than the females, they were the ones that I wanted to see, hear and smell, and whose every feature on their faces I wanted to capture on camera.

While the waiting was a damper, luck was still on our side, and indeed, as Charles promised, the experience was truly up close and very personal!

At the Ndutu Park, Southern Serengeti – not far from the Lake Masek Lodge where we put up – we stumbled upon two females and a male lion.

It was late in the afternoon, and we were already burnt out and wanted to head back to the lodge, but lo and behold, we had the three big cats greeting us.

The male had to choose one of the two for his mating session. After taking his pick, the rejected female walked away in a dignified manner and let the two begin their copulation.

Oblivious to everything else that was happening around us, and feeling almost like shameless voyeurs, we watched every moment of this passionate affair, with the dominant male on the top of the lioness.

One of us even timed the love making process, and another nudged me, in true Malaysian style about buying “nombor ekor” when I return to KL, just as I was focusing my camera at the spectacle to record every moment of this amazing scene.

The whole process, as my fellow travellers reported, was pretty brief, much to their disappointment. A herd of cows in the distance provided a momentary distraction for the two cats, but they continued with the deed for a short while more before the fun came to an end.

I had to tell a woman friend, who looked dejected, that she shouldn’t expect much since “this is a lion show, not tiger show, my dear sister. You expected one hour, ah?”

While we literally bumped into these three lions, it was much harder to spot them when we were looking for them. They hid behind rocks and cleverly camouflaged themselves, especially during the day, since there’s little reason for them to be roaming aimlessly if their stomachs are full.

Lions mating at Lake Masek, Serengeti.

“Lions need an average of 11lb to 15lb (5kg to 7kg) of meat per day, but they do not need to eat every day. If a lion makes a large kill, it may eat up to 66lb (30kg) of meat at once and then not eat for several days.

“Lions normally hunt large animals such as wildebeests, zebras, warthogs and Cape buffalo. They also eat smaller animals, ostrich eggs and fish. Lions are scavengers as well, and eat both animals that have died of other causes and carcasses robbed from other predators.

A hyena at one of the parks. Photo: Sin Cheang Loong

“Lions need to be versatile in obtaining food because hunting is not always successful. Individual lions make kills in about 17% of their hunts; lions hunting in prides are successful about 30% of the time,” reads a reference site.

I had the privilege of being driven around by Charles Christopher Joel, or Semchaa, his African name, who is a walking encyclopaedia on every plant, flower, bird and creature in Tanzania.

With his eagle eye and discipline, this multi-tasker could drive through dusty, bumpy terrain while training his eyes on nooks and crannies to look for lions and other exotic animals for us.

He can also provide a running commentary at the same time, but if we got bored and ended up chattering, he’d swiftly reprimand us for potentially disturbing animals in the vicinity.

At one point, he saw vultures circling high up in the sky, and alerted us that there had to be a lion, leopard or cheetah somewhere which had just made a kill.

Indeed, it was a male lion, holding parts of his prey in his mouth, and thanks to my photographer, Sin Cheang Loong, it was beautifully captured, although from a distance.

But our safari aside, lions are slowly disappearing from Africa. At the turn of the century, there were about 200,000 lions roaming the continent, but there are less than 25,000 left now.

According to National Geographic, lions are listed as vulnerable to extinction by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, which determines the conservation status of species.

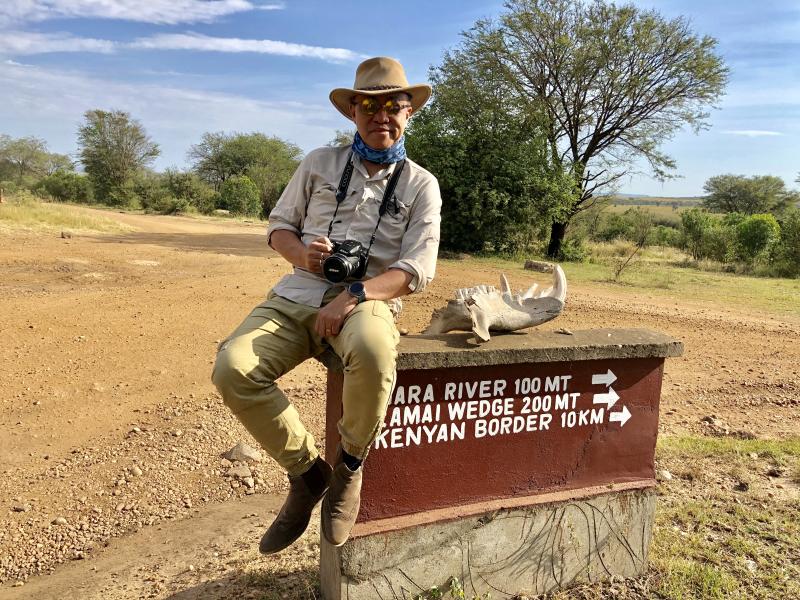

At the Tanzania-Kenya border. Photo: Florence Teh

To put things in perspective, the non-profit Wildlife Conservation Network notes that lion numbers have dropped by half since the animated movie The Lion King premiered in cinemas in 1994.

“Africa’s revered predators face myriad threats that put their very existence at risk. The decrease in lions’ wild prey for the bushmeat trade forces lions into dangerous contact with humans and their livestock in their search of food.

“But if the cats prey on cattle, they may be killed in retaliation – often by poison.

“And as human settlements grow, lions lose their habitat and see it fragmented, making it difficult for males to find new prides and mate.

“Poaching, too, poses a threat. Skin, teeth, paws and claws are used in traditional rituals and medicine, and there’s a growing market for lion parts in Asia as well.” As they say, once the demand stops, the killing will, too.

A gorgeous leopard spotted at the Serengeti National Park.

A mother giraffe and her child at the Arusha National Park.

In the end, I saw all the lions I wanted – one we saw in northern Serengeti eating in the distance, and another scene was of a family of three resting in bushes on top of rocks under shady trees at Kogatende, also in northern Serengeti.

So, all in all, we saw eight lions – an impressive number – including one at Ngorongoro Crater, which I viewed with my naked eye from a passing jeep.

According to The Guardian, the area of the world roamed by leopards has declined by three quarters over the last two and a half centuries, based on the most comprehensive effort yet to map the movements of the big cat.

It reported that researchers are shocked by the spotted hunter’s shrinking range, and that the decline has been far worse for several of the nine subspecies of leopards, including in other parts of the world.

“We found the leopard had lost 75% of its historical habitat, (and) we were blown away by that, (because) it was much more than we feared,” said Andrew Jacobson, a conservationist at the Zoological Society of London.

According to CNN.com, only about 7,100 cheetahs remain in the world and their numbers are swiftly dwindling, putting them at risk of extinction, according to new research.

Cheetahs should be re-categorised as “endangered”, instead of their current status as “vulnerable” on the list of threatened species maintained by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, researchers were quoted as saying.

Having done my research before the trip, I had realistic expectations, but in the end, I saw the cheetahs twice. The first time was a pair of brothers in northern Serengeti, where we also saw them mark their territory by peeing on a tree.

The second time was in the Ndutu area of southern Serengeti, in some marshy but dry grass land. It was a lone cheetah walking, which finally came to rest on a shady rock.

Cheetahs are fast becoming an endangered species.

Finally, we saw another pair at the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, just before sunset at the tail end of our trip.

I had less luck with the leopards – I only saw one on a tree that grew out of a large rock (also in northern Serengeti), which I managed to capture on my camera.

As I ended my two-week stay in Tanzania, I told myself that I needed to return to see these beautiful creatures again.

They belong here, freely and in their natural habitat, and not in zoos, which are jails for animals. We need to protect them more than ever now. Like in the case of many other animals that have disappeared forever, we don’t want them confined to the history books.

Zebras are easier to spot than some of the other animals at the Serengeti National Park.