Demand is picking up, but alas, consumers will pay more for basic goods

THE Prime Minister has been visiting the Pasar Ramadan at his Bera parliamentary constituency in southwestern Pahang since the fasting month began.

Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob knows them quite well and was quick to spot that some food sellers were missing this year.

“I found out that they were smallholders, but they have been busy on their oil palm lots because prices have soared,” he said.

That’s good news for the smallholders and it looks like this year’s Hari Raya celebrations will be the best in years for them.

Bera district, which borders Negri Sembilan, is only 2,214sq km but is home to many Felda oil palm settlers, with the plantations lifting the livelihood of thousands of rural folk.

The villagers have even set up a Facebook page where they share pictures and news of their lives. Among the postings are the side businesses they have gone into recently, including food manufacturing.

Although the breaking fast session was not the best time to ask the PM questions, the editors at his table took the opportunity to ask him about Indonesia’s decision to halt palm oil exports and its impact on Malaysia – among other things – on Sunday evening.

Last week, Indonesia made a surprise announcement. It decided to ban the export of palm oil from April 28 in a move to secure domestic food availability and control cooking oil prices.

It will have a worldwide impact, especially in Malaysia, as the global edible oil shortage situation has become acute since the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Indonesia accounts for 56% of the world’s palm oil production and accounts for 33% of oils and fats exports.

Malaysia is the second largest producer and can be expected to fill the void left by Indonesia.

As expected, palm oil prices have rallied, along with that of Malaysian commodities companies, even though Indonesia has now said that it may lift the export ban in a month or two.

If in the past, Malaysia and Indonesia have had to fend off anti-palm oil measures from the European Union, palm oil is now being seen as a viable alternative to sunflower and rapeseed oil, which come from Ukraine.

In the United Kingdom, supermarkets have had to limit the amount of cooking oil sold to shoppers.

While Malaysia will benefit greatly from the sharp plunge in sunflower supplies and Indonesia’s ban, we need to ensure that our producers do not go into a sale frenzy.

Selling wisely is pertinent as it will be good to reduce stocks. If done strategically, it will prolong the benefits, especially for the smallholders.

The total palm oil stocks in the country, according to the Malaysian Palm Oil Board is about 1.47 million tonnes, as of March.

For ordinary Malaysians, the concern is about government-subsidised cooking oil to meet local demand and to help blunt the impact of food inflation, especially among the lower income groups.

The government is expected to bear a cost of over RM2bil to maintain the cooking oil price this year compared to RM1.9bil in 2021.

But this is not just about cooking oil.

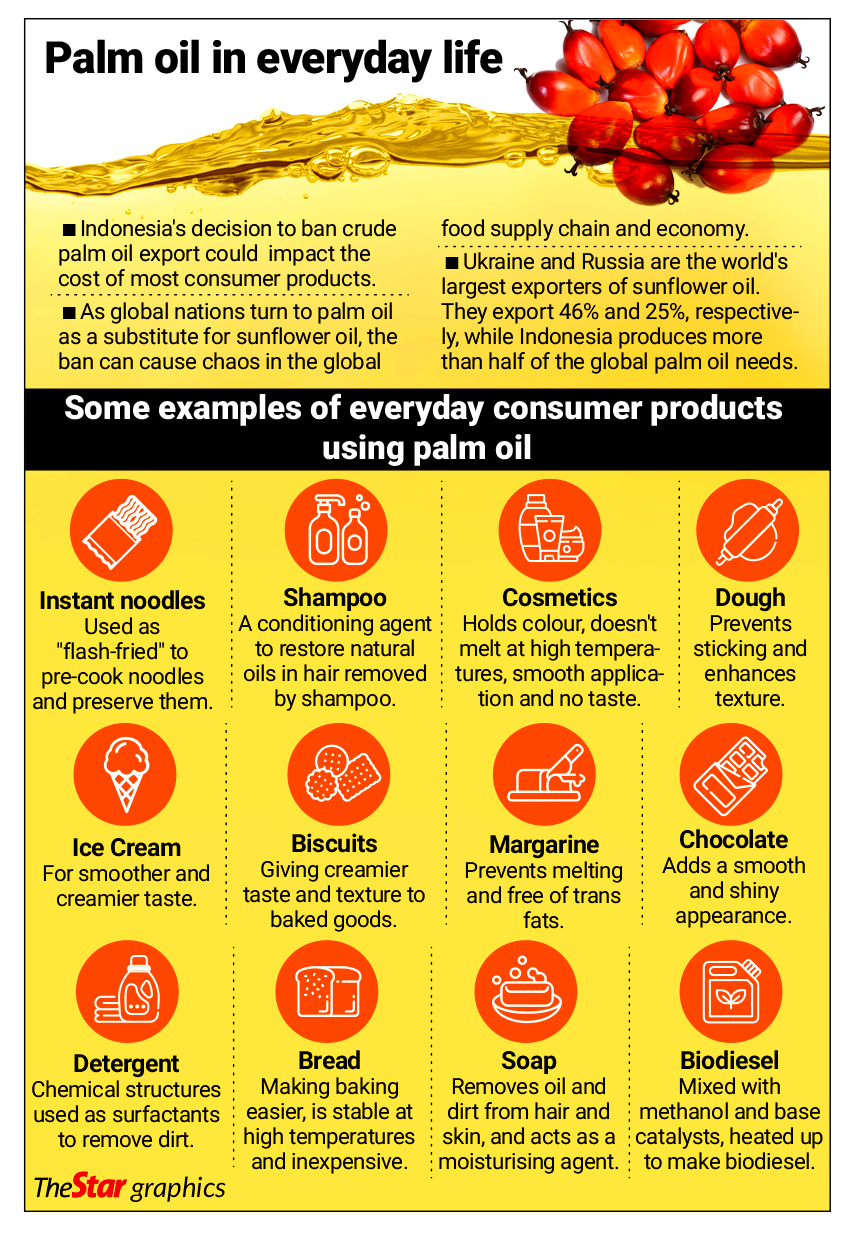

Palm oil is used as an essential ingredient for the production of instant noodles, ice cream, biscuits, peanut butter, margarine, chocolates, baby formula, lipsticks, detergents, soaps and even medicines, and these are not government-subsidised items.

The bad news is Malaysians will have to pay more for these items. It would be naïve to think that the increased cost of palm oil will not be passed on to consumers by these manufacturers.

Malaysian politicians are fond of reassuring the public with their standard, overused mantra of “all is all right, and it does not affect Malaysians’’.

But it may not be true this time.

Food inflation in January has accelerated at the fastest rate in four years in Malaysia, according to reports.

In 2020, Malaysia imported RM55.5bil worth of food products as compared to RM33.8bil worth of exports. To put it simply – the prices of almost all food items will or have gone up.

In February, Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers (FMM) president Tan Sri Soh Thian Lai warned that unless the cost of food and non-food items are kept under control, consumers should prepare themselves for price hikes of up to 10%.

Based on an FMM survey in December – even before the war in Ukraine – prices were on the rise with supply chain bottlenecks, higher logistic costs, soaring commodity prices and global energy and labour shortage, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, according to Free Malaysia Today.

Food aside, our top main imports are electrical and electronic products, chemicals, petroleum products and machinery appliances and parts.

We hope Malaysia will continue to benefit from higher global demand for our palm oil as over a million workers are involved.

The rise of palm oil price will boost our revenue but it will help if the government speeds up the entry of foreign labour to work in the plantations.

According to the South China Morning Post, Malaysian palm oil exports slumped to a five-year low last year and planters blamed this on the industry’s worst-ever shortage of workers.

The reality now is that, with a possible prolonged war in Ukraine, the world is desperate for more vegetable oil for food.

Prices have rocketed but it won’t help Malaysia if there are no workers to harvest the fruits.

It doesn’t look like Indonesia will impose a long-term ban simply because. For all the rhetoric and optics, its stock in February was at five million tonnes, which was the largest level since January 2021.

It needs to sell the stock. Palm oil has a short shelf life once processed into crude palm oil.

It can be anticipated that the export ban of Indonesian palm oil will not last because there is also insufficient storage capacities for growers and the mills are unable to obtain fresh fruit.

The lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic and Ukraine War are there for all to see – food security is very important and Malaysia needs to sufficiently grow our own food.