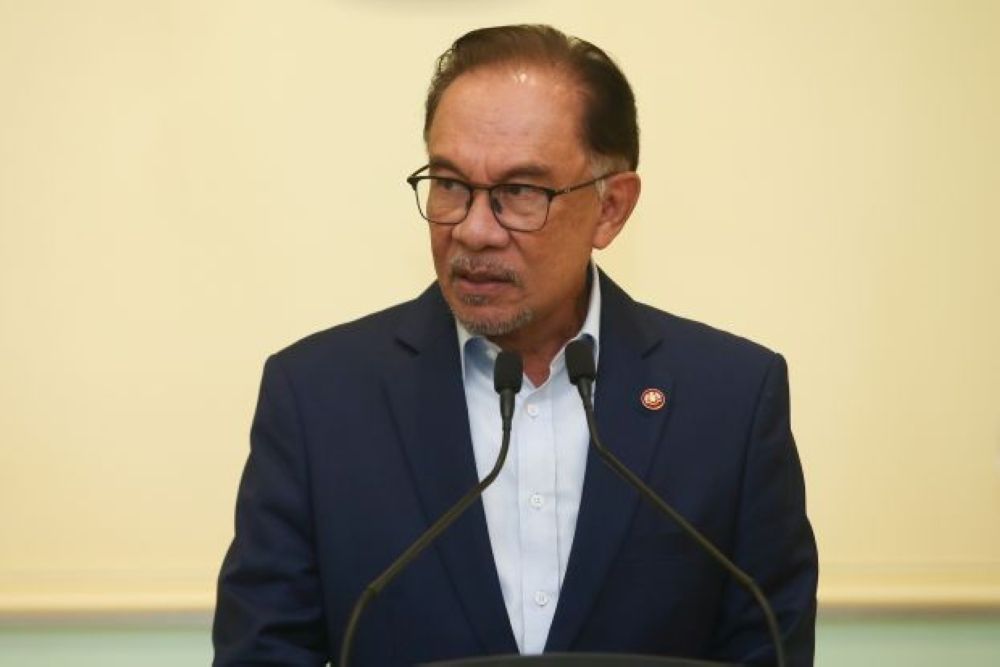

IF there’s one point that has been unceremoniously downplayed in the volumes of news reports and articles about the Prime Minister’s 100 days in office, it’s that Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim is the country’s first PM from a multi-racial party.

His predecessors have been from Umno, which led the Alliance and then Barisan Nasional coalitions.

Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia, which is headed by Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin, is mono-ethnic with Malay rights its predominant priority.

Anwar is the first PM to head a unity government which includes parties PKR has bumped heads with.

He has also taken on the job while Malaysia is facing huge financial constraints resulting from many factors, including the damaging 1MDB scandal.

As we take stock and assess his 100 days in office with his hits and misses, it’s important to remember how tightly bound his hands are.

The sound bites from his opponents suggest that the “traditional” race and religion card is being used yet again ahead of the elections in six states.

These politicians are compelled to believe that this is the most effective weapon – at least for Malay voters outside Selangor, Kuala Lumpur and the major cities.

Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, who quit Pejuang to join Putra, is still claiming the Malays are left behind although he had the chance to change that in his 22 years as PM.

He has insisted that the Malays have lost their dominance in politics in Malaysia, on top of their lack of economic control.

It’s quite amazing that the nonagenarian, who still doesn’t understand why he lost his deposit as a candidate in the GE15, has now claimed that the government may change electoral boundaries to reduce Malay constituencies.

The reality is that the Malays in Peninsular Malaysia will continue to dictate the political bearing of the country as they form the majority in 57% or 128 of the 222 parliamentary seats.

The Chinese have only 37 majority seats and the community’s population continues to shrink.

Sarawak has 31 and Sabah 25 seats with the breakdown of 10 Malay/Melanau, 10 Iban, six Chinese, two Orang Ulu and three Bidayuh, while in Sabah, the Chinese have three, non-Muslim nine and Muslims have 13 majority seats.

In 2021, it was reported that the number of Malays in Penang was increasing and has already outnumbered the Chinese by 0.7% and for sure, it will get higher.

We’d like to know if Dr Mahathir is making those assumptions to drum up the fear factor.

He’s not alone though. PAS president Tan Sri Abdul Hadi Awang is fond of that same MO.

The Marang MP has twice said that the unity government could collapse any time soon, but that prediction sounds baseless, so I don’t think many Malaysians will buy it.

His party has governed Kelantan for three decades and it’s incredulous how PAS can tell non-Muslims that it’s a model state when it’s one of the poorest.

It can’t even provide clean water, and one wonders how it can uplift the economic status of the Malay majority there.

Old guard politicians like Tan Sri Annuar Musa and Datuk Seri Shahidan Kassim have also used the same race and religion narrative, angling to have the optics of being champions for the Malays and Islam.

So, let’s give credit where it’s due. Race and religion haven’t been Anwar’s narrative, and instead, he has reminded Malays that corruption is the main threat.

His standing among the Malays remains a sensitive point as survey readings show contrasting results.

The issue remains a hot topic with Anwar insisting that his party’s research had placed Malay support for Pakatan Harapan at 31%. Last year, Bridget Welsh claimed Pakatan only polled 11% in GE15 and she was immediately challenged.

Merdeka Centre has found that the PM’s approval rating in a survey, held from Dec 26 to Jan 15, stands at 68% involving 1,209 voters across all ethnic groups.

All these surveys provide a barometer of the people’s opinions, although we may question the methodology and accuracy. That said, Malaysians are generally well-informed on issues.

The cost of living, job security and education were top concerns before GE15, and these haven’t changed within 100 days, so we don’t need desk-bound academicians to tell us that.

Ahead of the state elections, the unity government will depend on Umno to deliver the Malay votes, but it wasn’t able to do so in GE15.

Umno president Datuk Seri Dr Ahmad Zahid Hamidi has said that there were no factions in the party, but the consensus knows he was merely being politically correct.

He will have a small window of opportunity to bring the party together, following the party polls and a series of sackings and suspensions, to campaign in the polls.

It’s also not helpful for non-Malay leaders in the government to be talking about recognition for the Unified Examination Certificate (UEC) for Chinese independent schools and reforms in the civil service.

The timing isn’t right and there are no quick fixes, but more importantly, they don’t need the PM’s immediate attention.

His hands are tied and given the short 100 days, I think Anwar has done a decent job. Let’s not expect miracles.

The 100 days is an indicator to evaluate a leader’s performance, but the US-based Brookings Institute has also described it as “somewhat arbitrary and an artificial milestone” and as quoted by David Alexrod, a top aide during President Obama’s time, it is as an occasion of “having lots of attention but no significance.”

Its origin dates to President Hoover’s reign during the 1930s, whose 100 days were marked with bold and new actions.

Malaysia needs a fresh story for the world beyond race and religion and corruption.

We have a PM with extensive global goodwill. Let’s use it to the fullest.