Standing proud: The restored Suffolk House shines brightly in its restored grandeur.

AS A schoolboy taking the bus home, I would pass by the Methodist Boys School (MBS) in Jalan Air Itam almost every day.

I never knew about the existence of Suffolk House, where Captain Francis Light was said to have lived, nor understood its significance.

There was no mention of the mansion in my history textbooks. Furthermore, despite its granduer, it is off the main road, unlike the grand mansions along Jalan Sultan Ahmad Shah or Northam Road. It didn’t help that I had no friends studying at MBS.

But over the past decade, the loud calls to restore Suffolk House and efforts by non-governmental organisations to educate Malaysians about its historical significance, got my attention to find out more.

I finally stepped into Suffolk House a few months ago during one of my regular trips home. An upscale restaurant is now operating at the historic mansion.

The architecture of the 200-year-old building is simply stunning. The ambience and charm of the restaurant was worth the hefty bill that I paid for a dinner for eight.

I had an important guest from Kuala Lumpur with me and there were plenty of reasons to show what Penang has to offer besides street food.

After the last course, I closed my eyes and let my imagination run wild, and a few glasses of wine earlier definitely helped.

It was easy. After all, Light used to hold social gatherings – dances and events — at his residence, so did the subsequent governors of Penang and the Straits Settlements in the 1800s.

But there are now reports that say Light actually lived in a smaller house at the estate. The present mansion was only built much later.

Suffolk House was so named because Light was born in Dallinghoo, Suffolk in East Anglia. The house actually stands on the estate that was originally owned by Light, and where many Europeans stayed on because of their love for Penang.

But that night my mind wasn’t fixed on Light. Until now, each time I think of Suffolk House, questions would cross my mind about his Thai-Eurasian wife, Martina Rozells.

Little has been written about her and yet she probably played a huge role in the life of Penang’s founder.

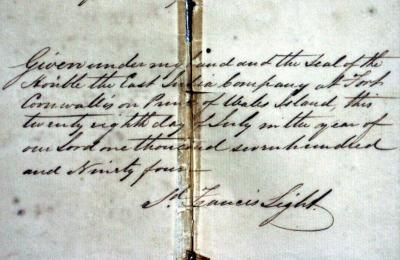

Flowy script: A letter signed by Light.

Light had met Rozells in Phuket, Thailand because it was his base for over a decade after he failed to convince the British of the importance of opening up Penang, which was an afterthought, in 1786.

Reading up about her life, I could not help but feel a strong sense of sympathy for her. Given her mixed ethnic background, she was probably a beauty but I am not sure she was given a fair deal by the British snobs.

Rozells has been referred to as Light’s wife but it was not clear whether she was his lawful wife or he simply regarded her as his wife. She had five children — three girls, Sarah, Mary and Ann and two sons, William and Francis Lanoon — with him.

When Light passed away in 1794 after suffering from malaria, his business partners, James Scott and William Fairlie, were the executors of his will.

According to some history books, the two transferred Light’s properties, including Suffolk Estate, to their own names and left Rozells in a lurch. In short, they cheated her.

She had to seek justice from the courts. But in the Victorian age, the fact that she was part Portuguese, part Thai and part French, was of no help. There have been suggestions by some writers that she was linked to Kedah royalty then, but this has never been substantiated.

She was a Roman Catholic while Light was an Anglican. In old Penang, the Anglicans reigned supreme. In their eyes, the marriage was not possible nor accepted, if indeed, there was a proper marriage.

In the book, Malaya’s First British Pioneer: The Life of Francis Light, HP Clodd wrote that Light “co-habited” with Rozells at least 22 years before his death in 1794 — as pointed out by historian Ooi Kee Beng in an article.

Interestingly enough, Light did leave Rozells a bungalow on the site next to the St Xavier’s Institution field.

In the book, Streets of George Town, a portion of Light’s will about this bungalow was reproduced:

“I give and bequeath unto the said Martina Rozells my bungalow in George Town with one set of mahogany tables, two card cables, two couches, two bedstead large and two small with bedding…. a dressing table and 18 chairs, two silver candle sticks, one silver teapot, two sugar dishes, twelve table spoons, twelve tea spoons, one soup spoon and all the utensils not under the stewards charge to be disposed of as she thinks proper without any limitation. I also give Martina Rozells four of my best cows and one bull….”

Ooi pointed out from Clodd’s book, “with little known about her, a shroud of mystery had grown around her over time”.

We do know that she bore him two sons and three daughters, the most famous of the children being William, who was the founder of Adelaide.

The book also mentioned, “Only two years after his death, Light’s estates were fast running into jungle to the certain loss of his heirs and the Company (British East India Company). His son-in-law, a General Welsh who married Sarah Light, would lament in 1818 that his wife’s siblings had lived to see every inch of ground and even his [Light’s] houses alienated from them. Rozells reportedly lived for several years on the land and in the bungalow bequeathed her by her common-law husband, and may have later married one John Timmer.”

Rozells was said to have held his wedding ceremony at the chapel in Fort Cornwallis in 1799. It was also said that after the service, the chapel was sealed off until now. No explanations had been found.

We can conclude that Rozells did not live an easy life in Penang. She failed to get her justice in the British-run court.

To keep her mouth shut, the British East India Company reportedly paid her a pension but kept the jewel in the crown.

In the eyes of British officials, Light did not marry Rozells but among the Eurasians and Thai community, she was regarded as his official wife.

It is sad that detailed and reliable information about her is almost non-existent even though she was the closest person to Light.

More information has surfaced over the past months — thanks to the work of Australian historian Marcus Langdon, who wrote that Suffolk House was built by (acting governor of Prince of Wales’ Island) William Edward Phillips. Philips was also the owner of Strawberry Hill on Penang Hill and not David Brown — Light’s partner.

Langdon had also written that Philips was the one who took over the pepper estate belonging to Light, on which stands Suffolk House, believed to have been built by Philips, who was acting governor of Penang in 1817.

In short – Light stayed at the Suffolk Estate but not at Suffolk House. Still, as I sipped my glass of wine at the restaurant on that rainy night, I could feel the presence of these iconic British figures who played a major role in making Penang what it is today.

Blame it on my imagination, the wet weather or simply the wine, but I could feel the many voices telling me to return to Suffolk House. I will, soon.