Remembered: Named after Sir Hussein Hasanally Abdoolcader who is also known as Malaya’s First Indian Knight, Jalan Sir Hussein is a quiet road off Jalan Mesjid Negeri.

Remembered: Named after Sir Hussein Hasanally Abdoolcader who is also known as Malaya’s First Indian Knight, Jalan Sir Hussein is a quiet road off Jalan Mesjid Negeri. Jalan Sir Hussein

IT IS one of the least known roads in Penang. After all, it is just a minor road, hidden from the busy Jalan Mesjid Negeri and further blocked from public view by several bungalows and government quarters.

But there are plenty of stories behind Jalan Sir Hussein, which is named after Sir Hussein Hasanally Abdoolcader, a prominent Penang lawyer in the early 20th century.

Before I go further, I would like to relate a most recent incident which prompted me to write about this particular road.

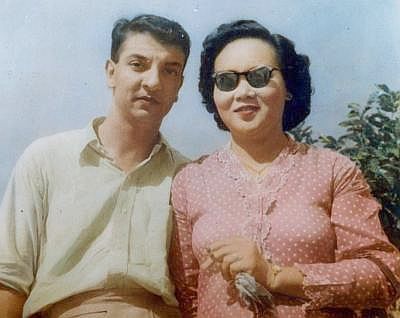

Lovebirds : Eusoffe and Haseenah in their younger days

Lovebirds : Eusoffe and Haseenah in their younger days I was in Kota Kinabalu last week and stayed at the Sutera Harbour Hotel. I met up with the food and beverage director, who introduced himself as Salim.

When I told him that Penang is my hometown and that I work in The Star, he got very excited.

In his very fluent Hokkien, he told me that he has been following MyStory and I should write about his grandfather’s road.

I looked a bit startled and he reiterated that the small road named Jalan Sir Hussein is named after his grandfather.

“I can really say it is my grandfather’s road,” he said.

We had a good time after that as he shared with me the stories of the Abdoolcaders, giving me personal anecdotes of the legendary family.

Sir Hussein was born in historic town of Surat, India in 1890. He was brought up in Malaya, where he received his early education at both the Raffles Institution in Singapore and the Penang Free School in Penang.

He went on to read law in Cambridge and soon returned to Penang to become a prominent lawyer, a community leader and politician.

Hussein was a member of the Straits Settlements Legislative Council and a member of the Advisory Council to the Governor of the Malayan Union.

Saying goodbye: Haseenah’s granddaughter Christina (left) and daughter Julie placing flowers on her grave on the third anniversary of her death.

Saying goodbye: Haseenah’s granddaughter Christina (left) and daughter Julie placing flowers on her grave on the third anniversary of her death. He held positions in various organisations, including the Association for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and the Mohammedan Football Association of Malaya.

Historian Tan Sri Khoo Kay Kim, in an article about the Indian Muslims, wrote that the Abdoolcaders were one of the most prominent families in the state. Others included the Ghulams and the Ghows, while in Singapore, they included the Munshis.

Their strong presence matched that of the Arab clans which included names like Alsagoff in Singapore and Hashim, Merican and Ariff, all prominent Jawi Peranakan families in Penang.

Hussein also made a name for himself in the Straits Settlement as the first Malaya Indian to be knighted by King George VI in 1948.

While the present generation of Malaysians, including those in their 50s and 60s, are unlikely to have met Hussein in real life, many would have come across, or at least, read about his son — the late Tan Sri Eusoffe Abdoolcader.

There is a book written on the legacy of the Abdoolcaders entitled Malaya’s Forgotten Sons: The Abdoolcaders of Hindostan in Malaya.

Like his father, Eusoffe also went to London to read law, graduating with a first class honours, before returning to Malaya to practise for 24 years before he was appointed as a judge. Salim, the Abdoolcader I met in Kota Kinabalu, is a nephew of the judge.

A former president of the Malaysian Bar, Hendon Mohamed, wrote: “The late Tan Sri Eusoff lived up to all that he promised. His years as a Judge brought an added, indeed glorious, dimension to the judicial pronouncements of the Court. His judgments were often hailed as literary works, his mastery of the English language, and of Latin, enhancing his deep but clear, lucid reasoning, no matter how complex the issues litigated before him. His life was one complete and total commitment to the law.”

As a reporter, who occasionally had to attend court hearings, I had the opportunity to follow some of cases presided over by Eusoffe.

Like everyone else, both lawyers and reporters, we were awed by his brilliance and intellectual prowess. But it was the aura behind the man that made him larger than life.

We are talking about an era when lawyers and judges still wore the horse-haired wigs and they all spoke impeccable English.

I can safely say these lawyers and reporters were terrified of Eusoffe as he would openly admonish anyone who failed to perform their duties.

In the case of reporters, anyone who did not report accurately the proceedings of the court would have to face his wrath.

The errant reporters, cringing in embarrassment, would be asked to stand up in open court and given a lecture in front of everyone.

In the case of lawyers, if they did not prepare their cases properly, “we would be chewed up alive by Eusoffe” as one lawyer recalled.

But there was a sad ending to his life and career. He is best-known as one of the five senior judge who were suspended in the 1988 judicial crisis as they crossed swords with then prime minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad.

To many, their suspension was seen as an end to Malaysia’s judicial independence although supporters of Dr Mahathir claimed they were not impartial in the first place.

In 2008, in what was seen as a step to heal the wounds, then PM Tun Abdullah Ahmad Badawi announced an ex-gratia goodwill payment to those judges suspended or sacked during the crisis.

Sadly, Eusoffe was no longer alive. In 1996, he committed suicide, apparently because he was profoundly depressed following the death of his dear Chinese wife, Haseenah in 1993.

Many of us would recall that Eusoffe used to place full-page advertisements in newspapers dedicating love poems, often in Latin, to his beloved wife.

But there is another well-known Abdoolcader — in this case, the infamous Siroj Hussein Abdoolcader, the late judge’s brother.

Like Eusoffe, he was sent to London to read law but Siroj ended up being arrested by the British for spying for the Russians, supposedly providing details of vehicles used by diplomats.

Siroj, who was working as a clerk at the Greater London Council, was accused of leaving messages at a tombstone in Portsmouth, England, for a Russian.

Siroj was jailed for three years and is said to be the first Malaysian to be jailed for espionage.

When Penangites pass by the minor road, they should take a second look at the road sign because Sir Hussein was certainly a major character in the history of Penang and the country.

Readers write

YOUR article on Pulau Jerejak revived memories of my working days there. Allow me to add a few interesting points. Although the inmates were of dubious background, I must stay they were generally a well-disciplined lot and followed the rehabilitative programme with much enthusiasm.

Tan Sri Ong Ka Ting made an official visit to the centre during my tenure there, when he was then the parliamentary secretary with the Home Ministry.

Volunteers from various religious bodies came passionately week after week to ensure inmates receive spiritual guidance. In hindsight, I wish to thank them for their valuable and often unnoticed contribution in this area.

The black dot of its penal history occured on Jan 5 and 6, 1982 when the inmates went on a rampage and burnt several dormitories. But, the riot was successfully quelled with the quick help from the police.

The centre was closed sometime in early 1992 when the inmates were transferred to Batu Gajah and Simpang Renggam Detention Centres to make way for tourism.

It is regretted that in their haste to develop Pulau Jerejak as a tourist resort, they neglected to preserve a portion of the said penal colony for future posterity. Hence, Malaysia has lost an important chapter of its penal history.

Donald Wee May Keun

P. P. A. Pulau Jerejak director

(January 1989 – December 1991)