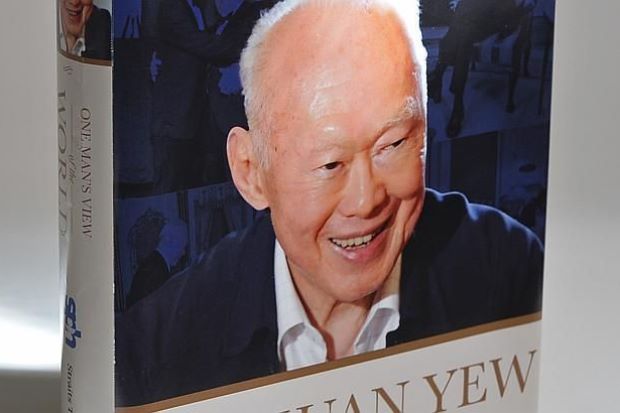

The cover of Lee’s book ‘One Man’s View of the World’.

The political demographic landscape has dramatically changed and will continue to move even more drastically in the coming years.

I HAVE just finished reading Lee Kuan Yew’s book – One Man’s View of the World, a collection of his analyses on various subjects across the world.

There is no denying that the former Singapore Prime Minister is a man of intellect. He is still sharp and insightful. He uses simple languages to offer his thoughts on subjects that would have turned out dull if presented by academics and diplomats.

Naturally, like many Malaysians, I started reading the chapter on Malaysia first, of which a part was conducted in a question-and-answer format.

There was one paragraph that stood out, which was his recollections on attending the meetings of the Council of Rulers in his capacity as Prime Minister of Singapore when it was still a part of Malaysia.

What he wrote is relevant to this day, and is something for all of us, especially those from the younger generation, to ponder upon even as we debate about the nation’s future following the outcome of the recent general election.

Between 1963 and 1965, as the PM of Singapore, he wrote that he had to attend the meetings of the Council of Rulers in Malaysia.

“The rulers who attended would all be Malays, dressed in uniforms and accompanied by their sword bearers. All the chief ministers had their traditional Malay dresses on and I was the sole exception.

“This was not mere symbolism. It was to drive home a point: This is a Malay country. Never should you forget that.”

But LKY’s memory has failed him somewhat. He was not the only non-Malay present. The Chief Ministers of Penang, Sarawak and Sabah were also non-Malays.

The Penang Chief Minister was Wong Pow Nee of MCA, who was the state’s first Chief Minister when Malaya was founded in 1957 and served until 1969 when the state fell to the then opposition party, Gerakan.

The first Sarawak Chief Minister was Stephen Kalong Ningkan, who was in office from 1963 to 1964. Sabah’s first CM was Donald Stephens, also from 1963 to 1964, who was then succeeded by Peter Lo Sui Yin. Stephens formed the United Sabah National Organisation while Lo was from the Sabah Chinese Association. So, in the period that Lee was referring to, he was certainly not the only non-Malay present.

Fast forward to 2013. Today, the only non-Malay and non-Muslim attending the Rulers Conference is Lim Guan Eng, the CM of Penang.

Chinese representation in the Federal Government, with the exception of those appointed from the ranks of non-politicians, has been reduced to zilch.

At the 13th general election, Umno performed slightly better to win 88 seats while the other component parties representing the Chinese – MCA, Gerakan and SUPP – suffered a bruising defeat.

The reality is that the majority of Chinese refused to vote for the Barisan Nasional, with the final analysis showing only 16% of the Chinese electorate went Barisan’s way. The Chinese vote is never permanent, and they have been known to swing their support at different elections.

But the strong swing against the Barisan was premised on the belief that they could help to form a new federal government if they threw in their lot with Pakatan Rakyat.

Many even returned from abroad and hoped to be part of history. They wanted to punish Umno but in the end, it was the Chinese-based parties they ended up punishing.

Not many were prepared to accept the reality that there were only 45 Chinese-majority seats in the 222-seat Parliament and even if every single Chinese had voted for the Opposition, there was no way the Barisan could be removed – unless the Malays decide to vote out the ruling coalition.

All that debate over the kind of electoral system, the gerrymandering process, whether it was Chinese or urban tsunami, and the rural advantage is academic when compared to the harsh political reality.

Last month, The Malaysian Insider news portal quoted Ibrahim Suffian of the Merdeka Centre as saying that its survey showed that the majority of first-time Malay and young Malay voters gave their support to the Barisan, suggesting that the Opposition has not done enough to convince young Malays that their future was secure with PAS, PKR and DAP.

Given the changing population profile, Malays will form an even larger chunk of new voters in future polls than the nearly two-thirds, or 64.17% of new voters, registered this year. In analysing the voting patterns of young and first-time voters, the Merdeka Centre, as part of its study of the recent general election, found that based on the electoral rolls used on Election Day, there were some 2.7 million more voters, and the influx of new voters was more pronounced in mixed and urban seats.

It grouped these voters into five voting channels with each representing an age group. Of the five channels or groups, the youngest group of under 30s was 64.17% Malay. The voter turnout overall for all races in this group of first-time and young voters was a hefty 83.22%. Of those, just over half, or 52.96%, voted for Pakatan.

Suffian’s advice to Pakatan was that the coalition would have to continue refining its position on Malay rights and cobble together a plan with an emphasis on job and wealth creation. The Pakatan, especially the PKR, will have to stand up to fight for Malay rights and positions if it wants to win the Malay votes. It has to compete with Umno, in other words.

The PAS ulamas, in the run-up to the party polls, have already served notice to their delegates to reject the so-called Anwarinas, PAS leaders said to be aligned to Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, which the hardcore have blamed for the party’s loss of Kedah and many other seats.

For an astute analyst like LKY, he would not have been surprised at the outcome of the general election.

There is much resentment in Putrajaya, until today, over how the Chinese voters had turned away from Barisan.

The Chinese, mostly in urban areas, on the other hand, see their decision as an outpouring of frustration over the many injustices with regard to opportunities from scholarships and university entrance to government contracts.

The Chinese also feel Malaysia has become more Islamised and is in danger of losing its moderate Malay identity. Money politics and corruption, which appear to have become entrenched, have also led to a sense of resentment.

The right-wing Malays, on the other hand, see the many compromises that have been made from the beginning of the nation, even over the name change from Tanah Melayu to Malaysia, the provision of citizenship and the guaranteed use of Chinese as a medium of instruction in schools, making us the one country beside China and Taiwan to do so.

As much as many of us want to see the future of Malaysia from a more Malaysian prism, the reality is that ethnicity will continue to be a factor with the Malay population growing bigger while the Chinese population continues to plunge.

In 2011, the national census revealed that Malaysia’s population doubled in size from 13.7 million in 1980 to 28.3 million in 2010.

Bumiputras numbered 17.5 million, or 67.4% of the population, while Chinese made up 24.6% of the population at 6.4 million, Indians 7.3% of the population at 1.9 million while “others” made up 0.7% of the population at 200,000.

Foreigners made up 8.2% of the population at 2.3 million – much more than the Indians.

Going by current trends, the projection is that the non-Malays will continue to drop further with some saying that by 2050, there could be 80% bumiputras in Malaysia and just 15% Chinese and about 5% Indians.

In fact, LKY, in his own words, predicted “eventually, the Chinese and Indians will exert little influence at the polling booths. When that day comes, with no votes to bargain with, the Chinese and Indians cannot hope to bring about a fair and equal society for themselves”.

Naturally, there will be those who disagree with this assessment as they strongly feel that race should not be the sole criterion in an election as Malaysia matures democratically.

They will point to the urban Malays who voted for the Opposition, citing the victory of PKR leaders in urban constituencies of Penang and Kuala Lumpur.

Race-based political parties, they believe, would fade away to make room for multi-racial parties.

But still, it is difficult for politicians aspiring for power to run away from the interests of the predominant race in this country. It’s the same in other countries as well.

In the book, LKY was asked if Malaysia becomes more homogenous, would there be a likelihood of the Malay privileges being let off, to which he replied: “You believe the majority will support leaders who want them to give up their privileges?”

And what about the Pakatan? LKY said “when it comes to the crunch, however, PR will not be able to do away with Malay supremacy” and “the moment the bluff is called and it is handed the full power to push ahead, it will either be torn apart from within or be paralysed by indecision”.

“Any party that takes the place of Umno and becomes the main party representing Malay interests will not act very differently from Umno.”

LKY cannot be faulted for his pragmatism, even if one does not agree with his politics.

The political demographic landscape has dramatically changed and will continue to move even more drastically in the coming years.

For the Chinese community, it will have to learn to be more strategic and also to be more realistic in its assessment of the community’s role in the country, as LKY had quite candidly observed.