THE outcome of the coming general election will be decided by the Malay and bumiputra voters, who form the largest electorate in the rural parliamentary constituencies. That’s exactly how the fight for votes will play out.

While the noisiest rumblings and largest rally turnouts will be in the urban areas, the campaign in the villages and deep interiors will weigh heavily in the hearts and minds of the people there. And ironically, this will take place with minimum fanfare.

The media will be discussing the elections from the viewpoint of Kuala Lumpur, city and town areas, attempting to sound authoritative, but they are unlikely to feel the pulse of the rural heartland unless they venture deep into these tricky terrains.

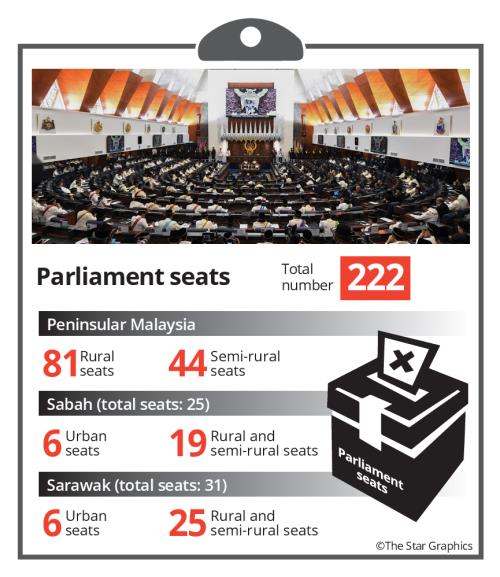

From the 222 parliament seats in the country, 119 are regarded Malay-majority. In Peninsular Malaysia, which has 156 parliament seats, 81 are rural and 44 semi-rural, totalling 125 seats.

In the 2013 general election, Barisan Nasional, through Umno, won 66 of the 81 rural parliamentary seats, or 81.5%, 14 in semi-rural (31.8%) and five urban seats (12.5%).

Another big chunk of the allocation comes from bumiputra seats in Sabah and Sarawak, which will be crucial in deciding GE14’s results.

There are 25 parliament seats up for grabs in Sabah. Apart from six, regarded as urban seats, the rest are rural or semi-rural.

Barisan holds 21 seats in Sabah, the breakdown including Umno (13), PBS (4), Upko (3) and PBRS (1), versus the Opposition’s Parti Warisan Sabah and DAP with two each.

Sarawak has 31 parliamentary seats with Barisan holding 25, mainly rural and semi-rural, while in the urban seats, DAP has five and PKR one.

That’s the math of the elections. These statistics will help in discussing the elections in a more educated, rational and analytical manner.

At present, Barisan has 130 seats. It is two short following the demise of Jelebu MP Datuk Zainuddin Ismail in December and the passing of Paya Besar MP Datuk Abdul Manan Ismail in February.

Unlike the rousing crowds at ceramah in urban areas, campaigning in the rural environment is done in quite the opposite fashion.

As voters are scattered in different parts of the mostly vast constituencies, candidates will have to make personal visits to see these people.

The incumbent MP usually knows the names of his constituents by heart with relationships having been forged over years.

Their presence at weddings or funerals is regarded critical in rural settings.

What has made the contest more interesting this time around is the field being populated with more three-way fights in many seats.

The multi-corner battles will help Barisan in most areas, but this also means the Malay votes will be fragmented.

These votes in GE14 will see a five-way split between Barisan, PAS and Pakatan Harapan. This is where the non-Malay votes will be crucial, making this demographic king makers then.

PAS has announced that it will run in at least 130 out of 222 parliament seats, exceeding the number contested by Umno in the last polls.

PAS research centre director Dr Mohd Zuhdi Marzuki revealed that the final number of federal seats (Gagasan Sejahtera – which comprises PAS, Parti Cinta Malaysia and Parti Ikatan Bangsa Malaysia – will collectively contest in the upcoming elections) has yet to be decided.

“PAS will contest in no less than 130 parliamentary seats. The remaining will be filled by Gagasan Sejahtera component parties, NGOs and eminent persons who stand with the coalition,” Zuhdi said.

PAS won 21 out of 73 parliament seats it contested in the 13th general election in 2013, though several have since defected to splinter setup Parti Amanah Negara.

Despite talk that Sabah and Sarawak are on shaky ground for Barisan, this is merely wishful thinking by detractors because the two states will surely deliver the seats to the coalition in GE14.

While the Internet has made it possible for rural folks to access all kinds of information, the narrative of politics of development remains relevant in both states. Simply put, bread and butter issues remain vital.

The rural voters still want to see their MPs every week, and not merely on the eve of the elections – that’s the status quo there.

The Opposition not getting their act together hasn’t helped their cause either. In Sabah, many multi-corner fights will unravel, dividing the opposition voters further.

For Pakatan, their strongest component party now is the DAP, which has 36 of the 72 seats, the rest including PKR (28), Amanah (7) and Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (1).

There’s every reason to believe the DAP will continue to be dominant, with the pressure tipped on Pribumi, particularly, to deliver the seats. Amanah looks like a slow starter in the race, compared to DAP and PKR.

After the polls, if the DAP remains the strongest and Pakatan is unable to form the government, then the growing expectations will hover over the Malay MPs from Pribumi, who will have to face their Malay constituents.

The dynamics of the equation will then be tested severely, like it happened in the past polls.

Despite the chatter about curbing party hopping, these self-serving political parties have merely encouraged defections, instead. Why else would both sides be reluctant to enact an anti party-hopping law?

Politics is about power and position, although its players would like us to believe that serving the people is priority.

The horse trading and deals will be part of the high-power game with the announcement of the results.

The seemingly unthinkable has happened, with foes becoming friends, so, expect the impossible to occur again.