It isn’t exactly crystal-clear waters, and certainly, it’s almost unheard of, but the waterfall at Lusong Laku, Belaga in Sarawak must surely rank as the most magnificent and majestic cascade in Malaysia.

The area deserves to be known as the Lost World of Sarawak because it’s virtually cut off from all forms of civilisation and remains one of the most remote parts of the state.

It took us nearly two hours to drive 142km from Bintulu, the coastal town in central Borneo, to Kampung Asap, a Penan resettlement.

From there, we hopped onto a four-wheel drive for a gruelling and treacherous six-hour journey that took us through logging tracks deep in the interior.

At a rustic coffee shop in Sungai Asap, we were cautioned about it being the last toilet stop because from there, we would have to answer nature’s call in the bushes.

We were also advised to make our last phone calls because we were going to go off the grid.

We’d be without GPS and would enter unfamiliar territory that was bumpy, dusty and dangerous. Also, we’d need to be on alert to avoid the beastly timber trucks that may come charging at us. Of course, instincts told us to pray it wouldn’t rain either, and that our vehicle wouldn’t break down during the roller coaster ride.

The plan was to reach Lusong Laku by sundown at 7pm, as darkness could potentially make the 270km trip more difficult, and of course, dangerous.

As we entered the jungle paths, we drove through timber camps and some farm huts, but there was little else.

Oh oh …. this is a rough patch! Going deep inside the Sarawak interior.

For an environmentally conscious urbanite like me, it was deeply upsetting to see the wanton logging still proliferating, and the trucks carting the logs passing by us was heartbreaking.

I couldn’t help but feel angry and sad at the destruction of the jungle and the ugly scars left behind by land clearing. Likewise, the displacement of the natives who made the jungles their homes, and the animals that live with them.

There wasn’t much to say. We kept silent, mostly, as we mourned the travesty before our eyes. It was hard to enjoy the panoramic view from above the tree tops of the rapidly depleting tropical forest.

The lush greenery of the jungle is at risk of excessive logging. Photo: FLORENCE TEH

Ironically, it’s these timber companies who have carved out the tracks which now make Lusong Laku and Sungai Asap more accessible to the people, where they can buy sundries and stock up on essentials.

However, the tracks were mostly badly maintained, and, on some stretches, planks were hastily put together as makeshift bridges for us to drive on.

And at times, we found ourselves precariously close to steep edges of ravines. Morbid thoughts kept playing in my mind of how we’d survive should our tyres slip and send us hurtling down. How long would it take for help to arrive? I shuddered to think.

The journey had taken longer than we expected because, much to our dismay, it rained. And the closer we got, the tougher the terrain became.

The timber tracks disappeared after a while, and the final 30km took us over two hours to navigate. In the darkness, the journey felt endless, and when we finally reached the village, it was almost 9pm.

Every villager seemed to be asleep, their homes pitch black, and a miscommunication almost left us having to sleep in the car – because the owner of a homestay wasn’t informed of our arrival.

Homestay in Lusong Laku.

But our host, Bulan Kulleh, sportingly cleaned up the house and then prepared dinner for us, which comprised wild boar soup, spicy ikan bilis and wild vegetables.

The majestic Lusong Laku waterfalls (called Wong Pejik in the Punan language, meaning waterfall) was just next to her home, and we could hear the roar of the cascading water.

The Punan are an ethnic group found in Sarawak and Kalimantan, Indonesia, but they are like the semi-nomadic Penan, who make up most of the people in Lusong Laku. The village itself is a resettlement area for these natives who had to leave their jungle homes to make way for the Bakun Dam construction.

Aerial view of the Lusong Laku waterfall and Sekolah Kebangsan Lusong Laku in Belaga.

Raging river of splendour, the Lusong Laku waterfall. Photo: FLORENCE TEH

Although I was exhausted, I woke up at 3am and couldn’t contain my excitement for dawn to break, so I could hurry out to see the incredible Lusong Laku.

I was prepared for the murky water because I knew the logging upstream had wreaked havoc on the environment, but the waterfall at the upper end of Sungai Linau was a sight to behold.

It’s simply breathtaking and spectacular and is likely the most incredible waterfall in Malaysia. It has been rightly named the “Niagara Falls of Malaysia”.

The fast-flowing water, which churned and rumbled as it thundered down the rapids, left me dazzled. I was drawn to make my way down the steep river bank to get better pictures.

Bulan, a Lahanan woman from Sungai Asap, advised me to be careful since a few people had been fatally swept away by the flowing currents.

With Cikgu Nazmie and Bullan at their house in Lusong Laku.

The writer was excited to finally see one of the greatest waterfalls in Malaysia, Lusong Laku.

Lahanans, the oldest inhabitants of Borneo belonging to the so-called Kajang group, are one of the smallest ethnic communities in Sarawak. But many regard themselves Kayans because of their proximity and marriage with the Kayans.

Excited, I was prepared to be a little reckless, and successfully made a slow descent onto the river bank.

My driver, Luhat Ajang, nervously kept his footing on the sandy shore to help me record a video, with the waterfall raging behind me while my colleague, Glenn Guan, was busily flying his drone to get the best aerial shots of the river.

Within walking distance from the waterfall is the Penan resettlement village, with its two rows of longhouses for 133 families.

With the Penan children at their longhouse.

The Penans have been described as the last aboriginal nomadic people in Sarawak who sustain their livelihood by gathering food from the forest, as well as hunting.

Displaced by the construction of Bakun and Murum hydro-electric dams, they have been resettled at Sungai Asap and Lusong Laku.

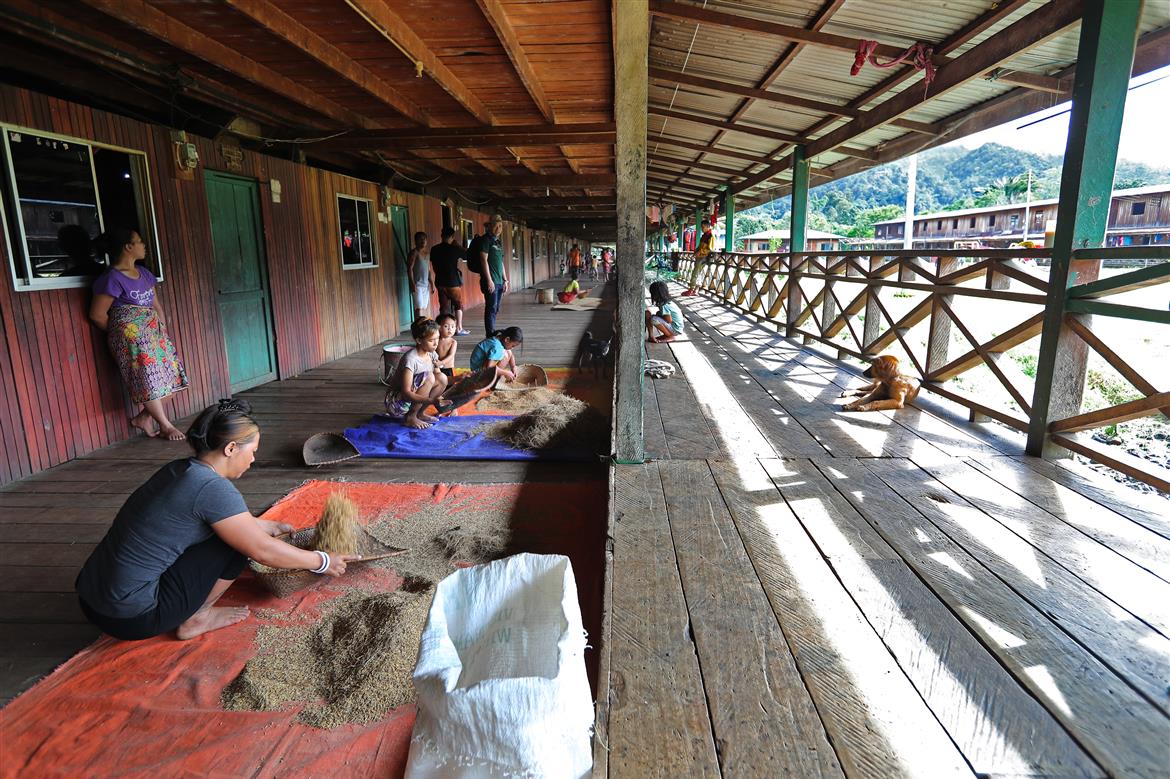

It has been reported that self-sufficiency in food production is a major problem for the Penans. To assist them, iM Sarawak came up with the Wet Padi Project to train the Penans in modern farming, which was implemented in 2015.

Going about their daily activities at the Penan longhouse.

Besides the Wet Padi Project, iM Sarawak also launched a food aid programme to cover their basic sustenance ahead of harvesting.

While Lusong Laku was once an important trading post before the war, the area has lost its shine, and very little information on the place is available. However, it is slowly getting known, thanks to the waterfall.

Saying goodbye to the kind folks of Belaga, Sarawak.

There is little chance of this incredible sight becoming a major tourist spot unless there are accessible routes and good commercial accommodation. This would also provide jobs to the people there. Its tourist potential will likely have authorities trying to rehabilitate the river and put an end to logging.

I also learned there was an inactive volcano crater around, but it is now covered by the jungle and no longer visible. There is certainly a need for more in-depth information on this stunning and picturesque spot, and for Sarawak to share its charms with Malaysia and the rest of world.