It was an invitation difficult to resist – to visit one of the last remaining wildest places on earth, and probably one of the last biggest intact temperate rainforests on the planet.

So, together with a group of faithful travelling companions, we flew a total of 17 hours, including two transits, to the Great Bear Rainforest in British Columbia in Canada.

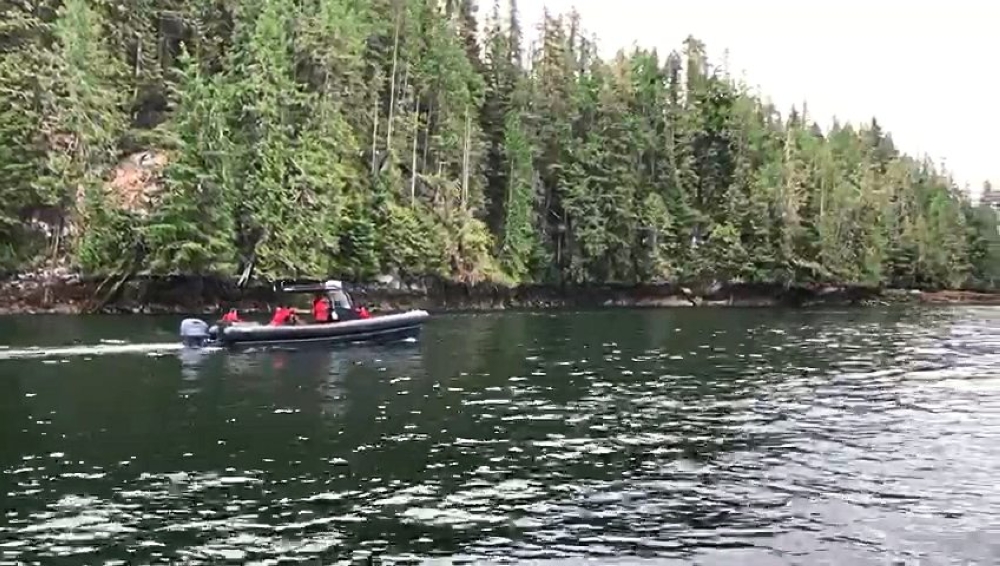

The only access to the islands of this 6.4 million-hectare land – the size of Ireland – is by boat or sea-float plane. But the logistics were no barrier since we were determined to set foot on one of the last frontiers.

This lush land of abundance is a sprawling wilderness located in the northwest corner of British Columbia, between Alaska and the northern tip of Vancouver Island.

It’s secluded and remote, and even hostile, at times. The meagre population of only about 18,000 comprises almost exclusively of indigenous folk who are called First Nation people. Their features very much resemble the Native Americans we are so used to seeing in the movies.

The grandeur of the Great Bear Rainforest.

The harsh weather has managed to keep the forests and seas in this area away from mass and destructive tourism. I was surprised that even many Canadians had not heard of this place.

The Canadian immigration officer who scanned my passport confessed that she had no idea what I was talking about or where I was even headed.

The plan was simple – we would hike up the thick forested hills and ease past the moss-covered rocks. Along the way, the trees, with their roots buried deep in the dark soil, would add to the visuals of rich flora.

The group had chosen a comfortable but hidden lodge in Nimmo Bay for the four-day adventure, a resort nestled in the southern part of the Great Bear Rainforest.

The itinerary included traveling on boats out in the freezing seas to look for humpback whales, orcas, porpoises, seals, sea lions and dolphins.

It is freezing but the only way to see humpback whales, orcas, porpoises, seals, sea lions and dolphins is by boat.

Along this coastal paradise, we had hoped to see black bears, and as much I dreamed of seeing wolves, my hopes were dashed when the organiser told us that it was impossible to see these gorgeous canines, except for their tracks. Lo and behold, I did see their paw prints on the ground, which proved a consolation in my books!

I was assured that July was the best time to visit this forest it being summer and all. But since this was Canada, I had packed thick clothing. As it turned out, it was still cold, even at this time of year. Indeed, it rained almost every day, and it was always windy and cold when I went out to sea daily.

The number one mission was to catch a glimpse of the orca, or killer whale – often mistaken for being a whale because of its name, though in truth, is the largest of the dolphin family – one of the world’s most prominent predators. (They are called killer whales because ancient sailors observed them hunting and preying on larger whales.)

But right off the bat we were warned that we’d probably only see their fins. The disclaimer was to lower unrealistic expectations. Besides, our boats had to stay 400 metres away from the marine animals, so spotting these magnificent creatures was always going to be a tall order.

It didn’t help either that there’s disturbing news of their dwindling numbers. Apparently, only about 74 of these toothed animals surge through the waters of British Columbia, according to reports.

Basically, we may not see them again if we don’t protect them. Threats include the lack of chinook salmon (their staple diet), the whir of boat engines and noises in general which interfere with their foraging exploits. Pollution is also a culprit which affects their ability to reproduce and battle disease.

Within the first 48 hours of our arrival, we decided that catching these mammals would be our priority, and no time would be wasted.

We saw humpback whales on the first day, but it was only on the second, while cruising Charlotte Straits, that we caught our first glimpse of wild orcas. Finally, there they were, wild and free with their family.

My disdain for show-performing killer whales has steadily grown over the years.

A family of killer whales at Numas Island. Photo: Liew Su Yen

The number of wild orcas, seen here at Numas Island, are slowly dwindling with only about 74 in the waters of British Columbia.

It’s plain animal cruelty and should be bereft of support. Why should we be surprised when performer animals turn on their trainers?

And aquariums and zoos are essentially prisons for animals. They don’t deserve to be locked up against their will.

I have great travelling companions who all share the same compassion and love for nature, and we kept reminding ourselves to be patient, and not be excessively excited.

Our boat coasted gently with the whales, where we watched them swim playfully and elegantly, without the fear of being hurt, or captured and sent to a distant aquarium.With their easily distinguishable black-and-white motif, large dorsal fin, and sleek and streamlined body, it was a privileged moment I wanted to soak every second of because I don’t know if I will ever be able to see them again.

Canadian rules are strict, and more importantly respected – our boat had to be at least 400 metres away from these mammals and no unnecessary noises are allowed because orcas are sensitive to sound.

I had to remind myself of the rules when I excitedly saw a black bear on the beach, looking for food on an island.

My guide advised me to calm down and said he was not going to steer the boat closer. Rules are rules, and this is Canada.

I had to get a little used to respecting these laws because as a Malaysian, I know the authorities talk about introducing new rules every other day, but almost none of them are enforced.

The Great Bear Rainforest in British Columbia, Canada is a lush land of abundance.

But despite the stringent laws to protect Canadian waters and backed by a population that is protective of its sea creatures, the animal’s flagging numbers suggest that this might all be too little too late.

Orcas are gentle and intelligent creatures which feed mostly on fish, though they hunt marine mammals such as seals, too.

Killer whales, found mostly in the Arctic and Antarctic regions, are highly social, and their populations are composed of matrilineal family groups, where the family members depend on older females – especially the grandmothers – on directions and foraging. The loss of females is devastating.

They are also clever and mate outside their families to avoid incestuous offspring, which could have a negative impact on them.

I was also lucky enough to spot two American black bears (Ursus Americanus), and unlike the killer whales, British Columbia has one of the largest populations of black bears in the world, their numbers anywhere between 120,000 and 150,000.

“Pretty much all of BC is considered ‘bear country’ with bears inhabiting everything from the coastal forests, through to the interior grasslands. From north to south and east to west in this province you’ll have a chance to see black bears,” says the British Columbia Conservation Foundation.The bears made a quick exit when they saw and probably heard our excitement, despite the distance. Our boat skipper told us, in no uncertain terms, that he would not attempt to come close to the bear on the beach, as “they will disappear, and we must respect their privacy.”

By now, it was very clear to me that Canadians go to great lengths to protect their oceans. There are rules even for fishing – a permit is required, even for a simple fishing outing.

There are also catch and possession limits, which include when and where you can fish, the species, size and number of fishes you can keep.

The giants weren’t the only animals to thrill me – I was also excited with the large number of harmless Moon Jellyfish or aurelia auruta, found in the shallow waters of Nimmo Bay.

The harmless and very beautiful Moon Jellyfish or aurelia auruta at Nimmo Bay.

I used my hands to scoop up some of these beautiful stingless transparent creatures, and I instantly recalled my adventure of swimming with thousands of stingless marine animals in the world’s largest jellyfish lake in Kakaban, East Kalimantan, Indonesia.

From killer whales and dolphins in the sea to bears and wolves in the forests, the Great Bear Rainforest also has its snow-capped mountains and glaciers, even during summer. Given everything we saw, it certainly lived up to its wild and remote identity.

And the only way to protect these animals and the mystic of this huge temperate rainforest is to keep humans away. It’s ironic how man, the orca’s purported saviour, is also its destroyer.