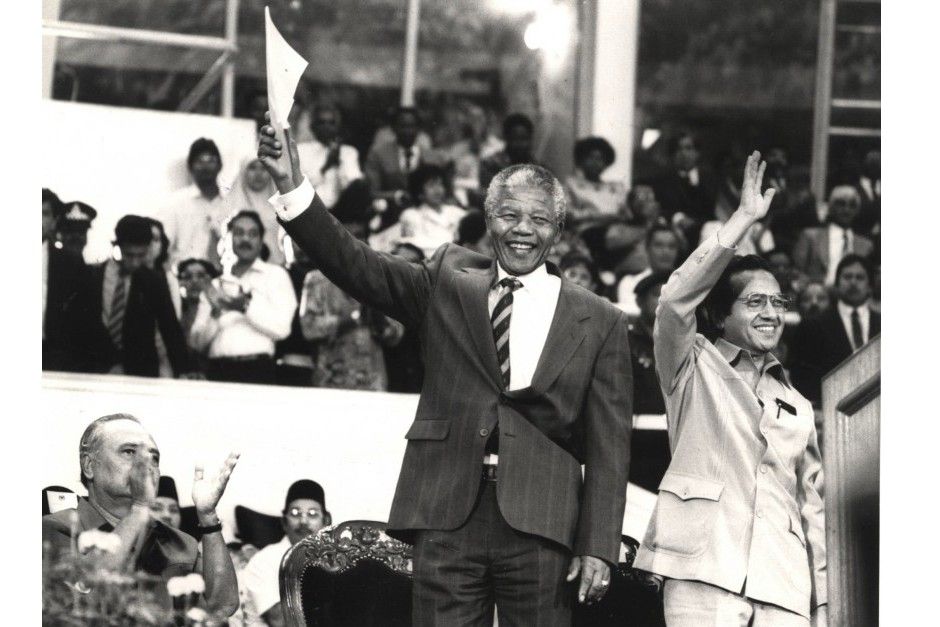

A file picture of Mandela (left) with Dr Mahathir during his visit to Malaysia in 1990.

IT hardly seems like three decades ago, but on the hot summer day of Feb 27, 1990, I stood on the tarmac of the Lusaka airport in Zambia to welcome African hero Nelson Mandela.

I was there as part of the Malaysian delegation led by then Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad to welcome Mandela, who was making his first trip abroad following his release from prison after serving time for 27 years.

Dr Mahathir was the only non-African leader invited to accord a hero’s welcome for this iconic figure and I was fortunate enough to be able to cover this historic moment as a journalist.

All six leaders of the African countries bordering South Africa, and Uganda, were on hand to greet this great man, who then Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda described as “a truly great son of Africa.”

Tens of thousands of Zambians turned out to get a glimpse of Mandela, who was heralded throughout Africa as the embodiment of the struggle against South Africa’s apartheid system of racial separation.

The atmosphere at the airport was electric. Zambia was chosen by Mandela as his first visit overseas because it had allowed the African National Congress (ANC), headed by him, to set up its “exiled” headquarters there.

Today, the world celebrates Nelson Mandela International Day to remember his achievements in working towards conflict resolution, democracy, human rights, peace, and reconciliation.

For Malaysia, we rebuked South Africa’s apartheid and refused to recognise its government from 1957, when we achieved independence.

Tunku Abdul Rahman took a strong stand against the apartheid government from Day One.

And in 1990, when Malaysia hosted the Commonwealth Heads of Government (CHOGM) summit in Kuala Lumpur, we invited a delegation of ANC leaders including Thabo Mbeki, whom I had the privilege of meeting and interviewing.

Mbeki would become the second president of South Africa, after Mandela, from 1994 to 2008.

The ANC was deeply grateful for the open support displayed by Dr Mahathir, who hosted the historic CHOGM meeting in KL, so it was no surprise that our then PM was given the honour of greeting Mandela at Lusaka airport.

But there’s one Malaysian name absent from the story of the formation of the South African government under Mandela.

That person is Tan Sri Lim Kok Wing, who played a crucial role in helping the ANC run its first general election.

ANC leaders were freedom fighters. To the white government, they were just terrorists, but the ANC had no experience entering a democratic election either.

Lim, who runs the LimKokWing University, recently found himself in a controversy over a huge poster depicting a caricature of him and a lion, with the words “King of Africa.”

It was put up by a cartoonist and had been there for months with little fanfare until the “Black Lives Matter” movement emerged, paving the way for discussion on diversity and inclusion issues.

It was perhaps a misstep, especially in the age of racial correctness, but the university has since apologised and taken it down.

One can call Lim all kinds of names, but a racist he is not.

His critics and former staff have described him as insensitive, a slave driver, self-centred and rude, while his admirers have said he’s a genius who is hardworking, far-sighted, patriotic and genuinely generous.

Certainly, racism has no place on his campus as he has students from more than 160 nations and many of his office staff are Africans. He can’t afford to be racist, even if he wants to.

And no Malaysian educationist would commit resources to set up branch campuses in Botswana, Sierra Leone, Lesotho and Eswatini, since many still see Africa as an unstable place to invest. Recently, Lim added more branches in Rwanda, Namibia and Uganda.

His fascination with Africa started when he was introduced to Mandela by Dr Mahathir.

Lim first met Mandela in 1990 in KL, and after the introduction, the latter asked Lim for creative support for South Africa’s first election.

Soon, Lim packed up and journeyed to Africa with an incredible mission – to ensure the ANC won big in the elections.

Lim’s important role in working with Mandela led the ANC to a historic victory, which ended 300 years of minority rule in South Africa in May 1994. Sadly, this achievement likely won’t make it into our history books, let alone our school textbooks.

Lim will say little of what he has done, except that he has been among those privileged to have worked with Mandela during his most glorious and defining moments.

After all, not many of us are blessed enough to be able to share a little anecdote of criss-crossing with Mandela and other ANC leaders on a campaign trail.

In the run-up to the ANC campaign, Lim produced 60 tonnes of billboards and posters to be put up throughout the country.

He campaigned with ANC leaders including Patrick Lekota, Thanon Mbeki, Barbara Masakela, Cyril Ramaposa and Joe Slavo.

He worked with Dr Popo Molefe, who chaired the elections campaign committee and went on to become the premier of the Northern Province.

Lim designed the election poster, which showed the faces of young Africans and argued his reason for including at least two Caucasian teenagers, even if this irked some hardcore ANC leaders. Adding insult to injury for them was being “told off” by a Malaysian.

On a few occasions, Mandela had to step in to tell his supporters that Lim could easily shut shop and go home if tensions remained high, but he assured his people that Lim knew what he was doing and was willing to give it a shot.

But the road to redemption for Lim was a long and winding one. To kick things off unceremoniously, the posters couldn’t be printed in South Africa because printers were mostly owned by Caucasians.

And posters of Mandela were either taken down by irate Caucasians or blacks who wanted them as keepsake, so it was a struggle to maintain his appearance.

The billboards and posters were eventually made in Malaysia from funding by Malaysian businessmen, and then sent to South Africa by a chartered plane from Kuala Lumpur.

I’ve heard South African leaders speak glowingly of the work done by Malaysia, although in a far from enthusiastic way. But one thing’s for sure – they’re certainly grateful.

Lim has been modest. He merely considers himself very privileged to have been involved in a small way in the sea change. But for me, as a proud History undergrad and a journalist, I have always insisted that the role played by Malaysia and this Malaysian, needs not only be recorded, but told, too.

As Lim embarked on his education crusade, I took a different path in this sprawling land. My thirst to understand Africa took off after Zambia.

Later on, I travelled to Botswana, Zimbabwe, Senegal, Sudan, South Africa, Egypt, Rwanda, Namibia and Uganda, as a journalist and traveller, and that’s just a fraction of what Africa has with its 54 countries.

Lim’s love for Africa didn’t end with the general elections of South Africa. He continued to play a significant role in the continent by transforming the lives of young Africans through the Limkokwing universities which he set up.

His African journey then took him to South Africa, where it all began with a new campus set up in the picturesque Warrenton.

I’m not a Dr Mahathir fan and I’ve written critically about some government to government deals, such as insisting Malaysia Airlines fly direct to Zimbabwe and Peru, which were all counterproductive decisions.

But his early emphasis on Africa was spot on, and as China makes its impact in Africa now – due to geopolitical reasons or its minerals – there’s no doubt that the continent offers a potentially huge market, and Dr Mahathir envisioned that.

As we, Malaysians, join the world to remember Mandela, we should also know about the small but crucial part played by our countrymen.

Giving credit where it’s due, we need to put aside politics and our personal prejudices and just record history as it unfolds.