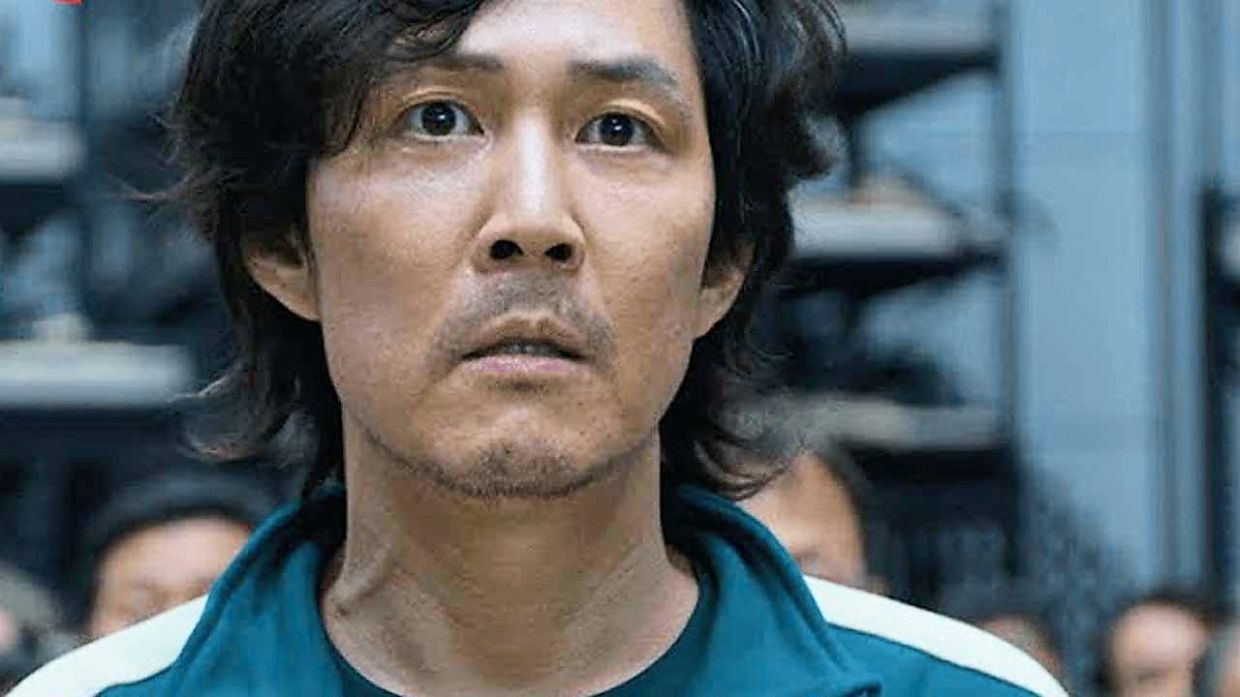

Positive message: A complex drama like Squid Game is about more than just killing. Through its flawed main character, Seong Gi-hun (pictured), it shows what happens when greed overcomes human values – not exactly an incitement to suicide is it? — Screenshot

PAS politicians never cease to amaze many Malaysians. From attempting to justify the act of corruption to blaming God’s wrath for flooding, they seem to have the most incredulous responses to issues.

Last week, PAS senator Mohd Apandi Mohamad blamed Korean dramas for teenage suicides in Malaysia.

After bingeing the nine-episode Korean drama and global blockbuster Squid Game, this writer only lost a night’s sleep, and didn’t end up a “blur sotong” (a Singlish phrase meaning someone who is clumsy or confused). I haven’t heard of anyone, teenage or warga emas, who was driven to suicide because, well, they are desperately awaiting season two.

If we go by Mohd Apandi’s logic, and had he watched the series, he probably only saw all the killings. He wouldn’t have seen its message – that greed should never overcome human values.

Life isn’t necessarily entirely black and white. So the main character, Seong Gi-hun (played by Lee Jung-jae), may have plenty of flaws, being a gambler, a failed father and an alcoholic, but he is also generous and helpful.

His main rival, childhood friend turned failed investment banker Cho Sang-woo (Park Hae-soo), even reminds Seong that his biggest failing is that he “cares too much about others”. By Cho’s deduction, this is a weakness – presumably worse than an addiction to alcohol and gambling – because in a world of conformity, success is measured by how much a person is valued or what institute of education they attended.

So I would not be surprised if politicians from PAS, who play to their audience, have a script to appeal to their voter base. They couldn’t care less what urbanites think about them. Why should they when they don’t contest in urban constituencies, where the people find them an odd bunch?

Apandi, who was apparently surprised by the brickbats he received from social media users, quickly clarified in the Dewan Negara that there were other factors that lead to suicide, and that he was not singling out Korean shows. Still wanting to stand his ground, though, he reportedly said “I am not saying Korean dramas or dramas trigger suicides, but they play a part.”

Oh, seriously – “a, jin-jja!” Still stubborn? After the fiasco, he tried to squirm his way out. Luckily, he didn’t blame the media for taking his words “out of context”, a line often used by inane politicians.

Earlier, Apandi had reportedly told the Dewan Negara that almost every South Korean film or drama incorporates elements of suicide, and Malaysian teens were aping that culture. He said many of the teens who took their own lives were “too influenced by films and dramas from Korea”.

According to the study “Youth Suicide in Malaysia” by Chua Sook Ning and Vaisnavi Mogan, during the period of March 18, 2020, when the first movement control order came into effect, to Oct 30, 2020, there was a total of 266 people who died by suicide, equivalent to around 30 suicides a month – almost one a day.

About one in four of these preventable deaths were adolescents aged between 15 and 18 years. The reasons in the suicide cases included debt issues, family and marriage problems, relationship breakdowns, and work pressures.

The study also found that younger individuals were at the highest risk of suicidal behaviour, with individuals between 16 and 24 years old being 4.8 times more likely to attempt suicide compared with people 65 years and above.

In 2017, suicide attempts were highest among Indians (17.9%), followed by Chinese (10.7%) and Malays (4.6%), with over 10% of suicides among bumiputras in Sabah and Sarawak.

Social factors attributed include unemployment, stress, social crimes, poor physical health, and social media, with Internet addiction especially increasing the risk of suicide attempts.

Still, let’s give credit to Apandi for bringing this up. It is an important issue. In the spirit of Squid Game, let’s not eliminate him but let him continue to play the game and move on to the next round. Every-one must be given a chance.

Perhaps he was merely trying to draw attention to his otherwise mundane speech, or he didn’t inform himself enough.

Depression is a cry for help, even if the person experiencing it doesn’t know it. So being receptive and offering a listening ear are the simplest things we can do to help someone ailing from it. Offering a support network comprising family and friends is crucial.

Mental health is a dire problem in Malaysia. The Covid-19 pandemic has generated a hike in suicide cases, no doubt about it.

Just look at the figures. The police recorded 468 suicides in the first five months of 2021 compared with a total of 631 in 2020 and 609 in 2019. On average, at least two suicide deaths occurred daily from 2019 to May 2020. In that time, at least 281 men and 1,427 women committed suicide, with 872 aged between 15 and 18, the police said.

Instead of blaming Korean dramas, we hope that PAS can draw up ideas and proposals on how we can thwart this malaise by identifying family members and people around us who could be suicidal.

The last thing we need is for PAS politicians to moralise and lecture Malaysians, and tell young people to stop watching Korean dramas after a day’s hard work.

Some entertainment won’t hurt lah, even if only to release pent up tension.

An interesting character in Squid Game is Player 244, played by Kim Yun-tae, who always seems to be on the right side of the Lord but who turns out to be brutal as the game progresses.